Recognizing hypoxic patients

Most critically hypoxic patients exhibit early warning signs of mild hypoxia before deteriorating. Recognizing and addressing these early signs can save lives and prevent the severe complications associated with untreated hypoxia.

“O2 sat reading is an essential part of vital signs and must always be mentioned along with whether on RA or O2 supplement and how much supplement the patient is on”

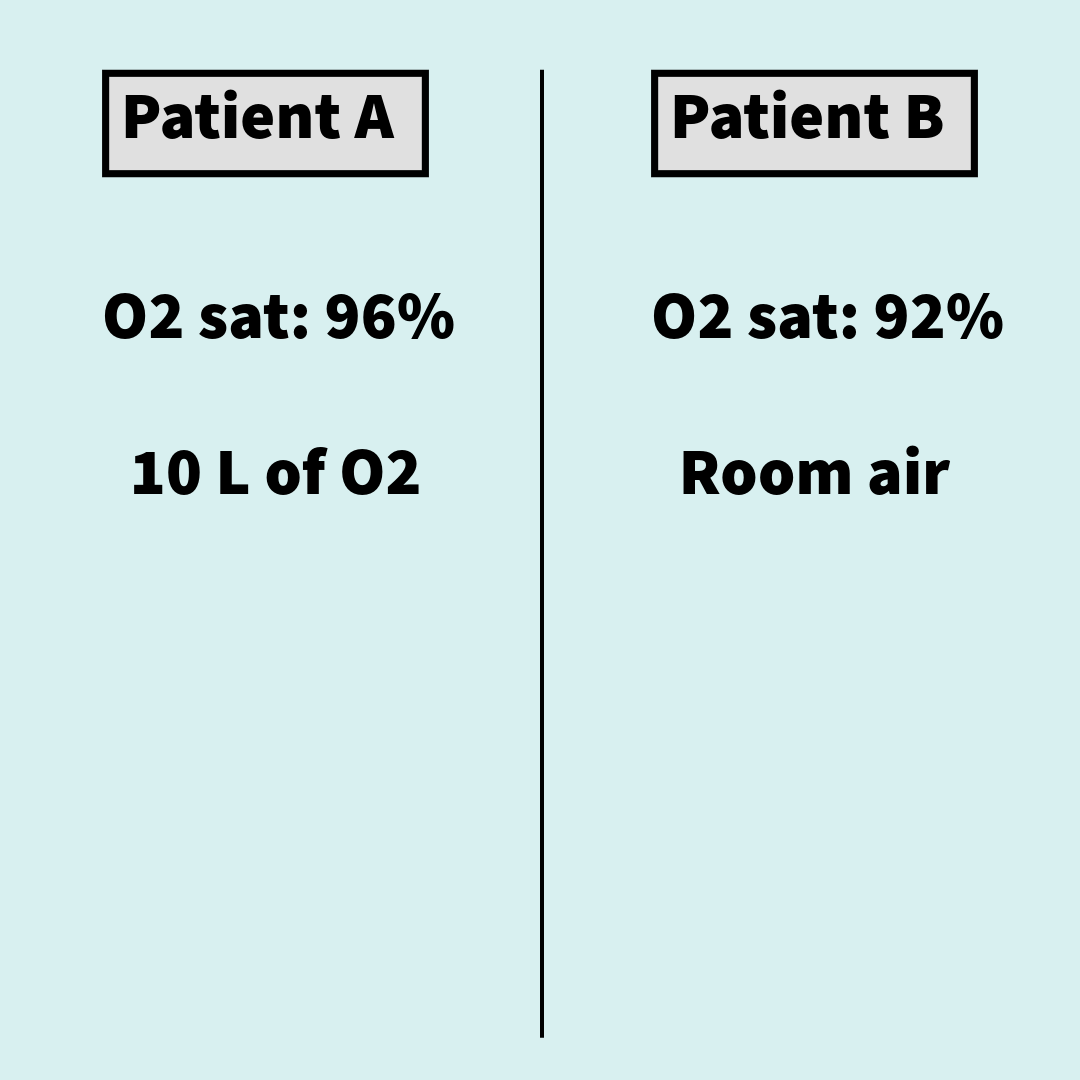

Take a look at patients A and B, can you tell who is more hypoxic?

You can see that patient A is worse than B despite the O2 sat of patient A being better than B because patient A requires 10 L compared to none in patient B.

Never accept pulse oximetry readings without knowing whether it is on RA or O2 and how much O2. I always check if my patients are on O2 supplements, how much, and ask the patient whether he/she uses home O2 and if yes how much O2 they use at home.

The moment I observe any of the following conditions, I need to determine the cause and address the underlying issue promptly:

- RA O2 sat < 95%.

- A patient who does not normally use home oxygen but now requires supplemental oxygen to maintain an O2 saturation of 95% or higher.

- A patient who normally uses home oxygen but now requires a higher oxygen flow than their usual baseline.

By doing this, you can prevent most patients from deteriorating due to untreated progressive hypoxia, effectively saving their lives!

We also need to pay close attention when nurses call about an oxygen-related issue. They may not explicitly mention a problem with oxygenation because, like physicians, nurses may vary in experience and may not always convey a sense of urgency. Let me provide some examples of what they might say during such calls:

- Hey doc, I am having a hard time keeping the patient’s O2 saturation up, I have to increase his O2 to 8 L/m but he’s doing better now.

- Hey doc, nothing urgent! I forgot to tell you that I have to crank the patient’s O2 a bit up but he’s doing okay now and his O2 sat is in the 90s

- Hey doc, my patient’s O2 sat dropped to low 80% a while ago, I put him on 2 L/min and it quickly improved to 92%, just wanted to let you know

- And of course, they may tell you straight to come and see the patient immediately because of very low O2 saturation

In all these scenarios, I always ask the nurse for the exact current pulse oximetry reading, the amount of oxygen the patient is receiving, a full set of vital signs, and how the patient is feeling. Then, I immediately go to evaluate the patient in person.

Stabilizing hypoxic patients

The moment I suspect, smell, or know my patient is hypoxic, I have to correct this hypoxia ASAP!

We categorize patients into:

- Stable patients: These are the patients whose nurses have already increased their oxygen supplementation and now have an O2 saturation above 92%, are asymptomatic, and have stable vital signs. They still need to be evaluated promptly to determine the cause of their increased oxygen requirement and to address it appropriately, preventing future deterioration.

- Unstable patients: O2 sat is low, they are symptomatic, and the rest of the vital signs are unstable, this is a medical emergency, leave everything and go see your patient, Over the phone, I instruct the nurse to increase the patient’s oxygen supplementation to the maximum capacity of the available oxygen delivery device. At a minimum, the patient should be placed on a 100% non-rebreather mask. If the patient is already on BiPAP, CPAP, or HFNC, I direct them to increase the FiO2 to 100%.

“Remember to activate the RRT if you have it at your hospital to speed up the response to your patient”

Upon entering the room, I ensure the patient is receiving the maximum oxygen supplementation available at the bedside, is connected to a monitor, the crash cart is nearby, and defibrillator pads are applied. If the Rapid Response Team (RRT) is activated, these steps should already be in place.

Proceed with endotracheal intubation immediately if hypoxic respiratory failure is associated with:

- Encephalopathy, whether the patient is agitated, lethargic, or obtunded. Begin bag-valve-mask ventilation immediately if the patient is extremely lethargic or obtunded.

- Recurrent aspiration due to persistent vomiting.

In these situations, don’t hesitate—proceed with intubation immediately.

If the patient is not encephalopathic, rapid action is still crucial to prevent further deterioration and, if possible, avoid the need for mechanical ventilation.

Quickly assess the patient by listening to their lungs (if possible), checking for any fluids or blood products being administered, and gathering a brief history from the nurse. Then, position yourself at the foot of the bed to take control of the situation. All of this should be accomplished within 30 seconds.

If the patient’s O2 saturation remains below 90-92%, escalate to the highest level of oxygen delivery available. Here’s what I mean:

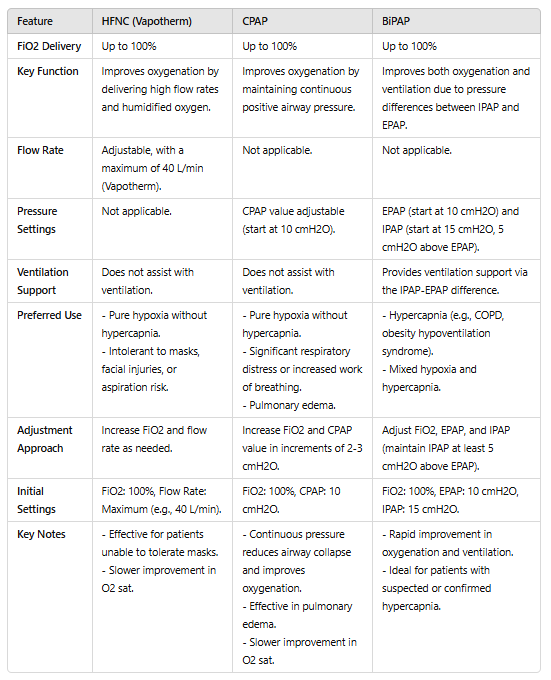

At my facility, we have a high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), CPAP, and BiPAP, all capable of delivering 100% FiO2. The choice between them depends on the underlying condition:

- Choose BiPAP over CPAP or HFNC if there is confirmed or suspected hypercapnia (e.g., COPD or obesity hypoventilation syndrome) based on ABG results or clinical suspicion. Use BiPAP until ABG results are available.

- Choose CPAP or HFNC for pure hypoxia without hypercapnia:

- CPAP is preferred if the patient has significant respiratory distress or increased work of breathing.

- HFNC is ideal if the patient cannot tolerate a mask, has facial injuries, or is at high risk of aspiration.

In the heat of the moment, choosing any of these devices is acceptable. If you’re feeling stressed or overwhelmed and can’t decide, default to any device—it will suffice until the patient stabilizes.

Remember, during this acute phase, I’m less concerned about inappropriately reducing CO2 (hypocapnia) because it isn’t immediately life-threatening. Hypoxia, however, can be fatal

What settings should we use?

Regardless of the device chosen, all patients should initially be placed on 100% FiO2. Here’s how to set up each device:

- HFNC (High-Flow Nasal Cannula):

Specify the flow rate in addition to FiO2. The maximum flow rate depends on the machine’s brand. For example, at our hospital, we use Vapotherm, which allows a maximum flow rate of 40 L/min. Start with the maximum flow rate. - CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure):

Set the CPAP value. A good starting point is 10 cmH2O. - BiPAP (Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure):

Set both the EPAP (equivalent to CPAP) and IPAP values:- Start with an EPAP of 10 cmH2O.

- For the IPAP, add 5 cmH2O to the EPAP to achieve a PIP (peak inspiratory pressure) that is 5 cmH2O higher than the EPAP. For instance, begin with 10/15 (EPAP of 10 cmH2O and IPAP of 15 cmH2O).

These initial settings provide effective oxygenation and ventilation while allowing for quick adjustments based on the patient’s response.

There are two ways to improve oxygenation:

- The quick way: Increase the FiO2.

- The gradual way: Increase the flow rate on HFNC, the CPAP value on the CPAP machine, or the EPAP on the BiPAP machine.

It’s important to note that only BiPAP can assist with ventilation due to the pressure difference between IPAP and EPAP.

Remember, oxygen saturation may not improve immediately. Stay calm—it can take several minutes for O2 saturation or pO2 levels to increase. As long as there is steady improvement, you can be reassured.

If the O2 saturation isn’t improving or is declining despite being on maximum HFNC, switch to CPAP or BiPAP using the previously recommended settings. If the patient is already on CPAP or BiPAP, consider increasing the CPAP or EPAP value in increments of 2-3 cmH2O. For BiPAP, ensure that the IPAP is adjusted to maintain a PIP at least 5 cmH2O above the EPAP.

Remember at any point the patient becomes encephalopathic to proceed with endotracheal intubation.

When to consider intubation and mechanical ventilation in patients who are not encephalopathic?

The decision to proceed with mechanical ventilation isn’t always clear-cut, multiple factors need to be considered including code status, mental status, and hemodynamic stability.

In general, mechanical ventilation should be strongly considered if a patient’s oxygen saturation remains below 80% despite maximum oxygen support and there are no signs of clinical improvement. However, during the COVID era, we encountered patients with oxygen saturations in the 70s who were managed without intubation. Always use your clinical judgment to guide the decision.

Let’s compare two examples:

- Patient A initially had an oxygen saturation in the 40s. After being placed on CPAP at 10 cmH2O with 100% FiO2, their O2 saturation began to progressively improve, reaching the high 60s and continuing to rise. For this patient, I would give more time, as their oxygen levels are steadily improving with oxygen therapy and treatment of the underlying cause.

- Patient B started with oxygen saturation in the low 80s, but despite CPAP at 10 cmH2O with 100% FiO2, their O2 levels continued to decline, dropping to the 60s and then the 50s. This patient will require intubation and mechanical ventilation to stabilize their condition.

Don’t hesitate to ask the people around you if we should proceed with intubation including your colleagues or nurses.

Workup and Management of the underlying cause

When stabilizing a patient’s oxygenation, it’s equally important to investigate the underlying cause. Here’s a step-by-step framework:

Initial Steps to Stabilize and Investigate

- Gather a brief history from the patient’s nurse.

- Listen to the patient’s lungs for clues.

- Inspect the room for IV fluids or blood products being administered.

- Order essential diagnostics:

- Stat chest X-ray (CXR)

- Electrocardiogram (EKG)

- Arterial blood gas (ABG)

Understanding the Causes of Acute Hypoxemia

While hypoxemia can result from five mechanisms—hypoventilation, V/Q mismatch, right-to-left shunt, diffusion limitations, and low-inspired FiO2—clinical practice often reveals a more focused list of causes.

Suspect one of the following Conditions in patients who develop sudden shortness of breath and severe acute hypoxic RF:

- Pulmonary edema (cardiogenic or non-cardiogenic)

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Pneumothorax (PTX)

- Lung collapse or atelectasis

- Large pleural fluid collection (e.g., pleural effusion, empyema, or hemothorax)

Breaking Down the Conditions

1. Pulmonary Edema

- Clues to Diagnosis:

- Orthopnea, crackles on lung exam, jugular venous distension (JVD), peripheral edema.

- Presence of IV fluid or blood product infusions.

- Management:

- Stop IV fluid or blood product infusions immediately.

- Administer 80 mg IV furosemide.

- Use CPAP if no CO2 retention is suspected.

- Start a nitroglycerin drip if blood pressure is elevated.

- Perform diagnostics: EKG, chest X-ray, cardiac enzymes, and echocardiogram.

2. Aspiration Pneumonia

- Clues to Diagnosis:

- Reports of choking or visible vomiting around the mouth or bed.

- Management:

- Proceed with intubation if the patient is actively vomiting or aspirating.

- If intubation isn’t required immediately, initiate HFNC at maximum settings.

- Avoid CPAP/BiPAP if the patient cannot clear secretions unless a nasogastric tube (NGT) is placed for suction.

- Start antibiotics to address potential infection.

3. Pneumothorax, Atelectasis, or Large Pleural Fluid Collection

- Pneumothorax (PTX):

- Clues: Absent breath sounds on one side.

- Management:

- Confirm diagnosis with CXR and place a chest tube immediately.

- For tension PTX, perform needle decompression if chest tube placement is delayed.

- Use maximum HFNC to manage hypoxia until a chest tube is in place.

- Atelectasis:

- Clues: Weak cough, difficulty clearing secretions, tracheal shift toward the affected side.

- Management:

- Initiate chest physiotherapy (CPT), suctioning, mucolytics, and breathing treatments.

- If no improvement, consult pulmonary for bronchoscopy.

- Large Pleural Space Collection:

- Clues: Tracheal shift toward the unaffected side.

- Management:

- Perform therapeutic thoracentesis, ideally with chest tube placement.

- Key Considerations:

- Pleural effusion: Common with malignancy, cirrhosis, or heart failure.

- Empyema: Severe leukocytosis, pleuritic chest pain, systemic illness.

- Hemothorax: Often linked to trauma or thoracic procedures.

4. Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

- When to Suspect:

- Hypoxia unexplained by lung exam or CXR findings.

- Management:

- If suspicion is high and there are no contraindications, start full anticoagulation immediately.

- Obtain a chest CTA, but ensure the patient is stable enough for the scan.

- Use bedside POCUS to assist in diagnosis if trained.

For all these patients, keep them NPO (nothing by mouth) until they are more stable. If aspiration was the underlying issue, request a speech therapy evaluation. Transfer the patient to a higher level of care, typically the ICU; however, an IMC (Intermediate Care Unit) or step-down unit may be appropriate for select patients. A comprehensive panel of blood tests is usually ordered, including:

- CBC (Complete Blood Count)

- CMP (Comprehensive Metabolic Panel)

- Cardiac enzymes

- Lactic acid

This ensures thorough assessment and monitoring of their clinical status.

Ensure continued treatment and monitoring as needed based on the patient’s condition. For example:

- Administer additional diuretics for persistent pulmonary edema.

- Perform more frequent chest physiotherapy (CPT) or consider bronchoscopy if indicated.

- Confirm that a chest CTA is completed and promptly follow up on the results if PE is suspected.

Adjust care dynamically to address the evolving clinical situation.

Further workup and treatment may be necessary based on the findings. For instance, if the EKG indicates evidence of an acute MI, follow the appropriate treatment guidelines.

Ensure to order a follow-up ABG and adjust treatment as needed. As the patient stabilizes:

- Gradually wean FiO2 down as tolerated.

- Avoid reducing the flow rate on HFNC or the CPAP/EPAP values until FiO2 is decreased to 60%. Once FiO2 is at this level, begin weaning both the FiO2 and flow/pressure settings together.

This approach helps optimize oxygen delivery while ensuring patient safety during recovery.

Transfusion Medicine Made Simple: Essential Guide for Clinicians

Eight EKG patterns in acute MI we can’t afford to miss!

The top three antiemetics I rely on!

The use of 3% NS in hyponatremia, when and how.

The inpatient treatment of hypercalcemia

Hyperkalemia-induced EKG changes

The Proper Way to Replace Magnesium

Non-insulin diabetic medications