Learn the 8 bad lab habits in hospitals that waste resources and rarely change management. Discover smarter, evidence-based alternatives to improve patient care and reduce unnecessary testing.

How to manage acute pain in inpatient settings

Introduction

I can’t remember the last time I finished a shift without a call about a patient in acute pain. In this post, I’ll share a practical, easy-to-use guide to help you choose the right analgesia for your patients.

Pain severity scale

The first and most important step—often overlooked—is to assess the severity of pain using a standardized pain scale. In the hospital, this is typically a numerical rating scale, where patients are asked to rate their pain from 0 to 10. A score greater than 6 is generally considered severe.

Mild pain

This is pretty straightforward. Oral acetaminophen alone or in combination with a low-dose oral NSAID can be used. An ideal mild pain regimen would consist of:

- Acetaminophen 650 mg orally every 4 hours as needed.

- Ibuprofen 400 mg orally every 4 hours as needed.

The nurse should administer either option, but not both at the same time. They may alternate between the two if needed.

Personally, I prefer the sole use of acetaminophen in the mild pain category.

Moderate pain

A high-dose Oral NSAID with or without low-dose IV acetaminophen.

IV NSAIDs are an option here, as well. In such a case, oral NSAIDs should be discontinued. An ideal regimen would consist of:

- An NSAID (Pick one):

- Naproxen 500 mg orally twice daily as needed.

- Ibuprofen 600 mg orally every 6 hours, or Ibuprofen 800 mg orally every 8 hours as needed.

- Ketorolac 15 mg IV every 6 hours as needed.

- If NSAIDs are contraindicated or inadequate, Acetaminophen 650 mg IV every 6 hours as needed can be added.

“Don’t use oral and IV NSAIDs together”

Severe pain

This is the category where opioids should be used! Opioids should be reserved for severe pain only, including oral & IV opioids! This may seem odd, as a lot of hospital pain protocols include low-dose oral and IV opioids for moderate pain. Please avoid that unless there is a contraindication to use acetaminophen and NSAIDs!

Why am I saying this?

Adding opioids for moderate pain will likely lead to unnecessary and avoidable use of opioids!

Just imagine your patient is having moderate pain based on the assessment scale, and you have the option to pick between a low-dose opioid or an NSAID, most of us will unconsciously lean toward picking the stronger analgesic, which is an opioid here, although a dose of naproxen would have been probably adequate!

So, unless there is a contraindication to use NSAIDs or Acetaminophen, reserve opioids for severe pain only, please.

But does that mean opioids are the only option for severe pain? Of course not!

High-dose IV Acetaminophen and IV NSAIDs are pretty effective in severe pain as well.

So an ideal regimen for severe pain analgesics would consist of:

- IV Acetaminophen or IV NSAIDs (First line)

- Oral opioid (Second line)

- IV opioid (Last to use).

I will go for IV NSAIDs or Acetaminophen first, oral opioids second, and IV opioids are our last resort if the patient’s acute pain remains inadequately controlled

Remember that NSAIDs are first-line analgesics in the following conditions:

- Renal colic, IV Ketorolac in particular, is effective here.

- Musculoskeletal pain like arthritis pain, pleuritic-type chest pain, rib fracture, and muscular strains.

- Incisional post-operative pain.

Acetaminophen is particularly effective in most types of headaches alone or in combination with caffeine.

Also, the location of pain may warrant analgesia avoidance, like chest pain of cardiac origin, where NTG should be used instead.

Now, which opioid should we use and what dose? I refer you to an older post where I discussed the use of opioids. You can read it here

Persistent severe pain

In persistent severe pain where the patient keeps requiring recurrent doses of opioids despite treating or while treating the underlying cause of pain, we need to try to reduce the pain level with other means and consequently reduce the need for IV opioids:

- Adding scheduled (Not PRN) oral acetaminophen or oral NSAID, remember to discontinue their IV equivalents.

- Adding Gabapentin

- Adding a scheduled low-dose oral opioid can be considered if previous measures didn’t help reduce the use of IV opioids.

Let me give you an example:

A 64-year-old lady was admitted with a pelvic fracture, she’s in severe pain her severe pain regimen consists of the following:

- Ketocorolac 15 mg IV every 6 hours as needed

- Oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg PO every 4 hours as needed

- Morphine 4 mg IV every 6 hours as needed

You reviewed her chart and found that she received 12 doses of IV morphine over the last three days, her nurse reported that IV morphine is the only thing keeping her pain under control and she asked you if there’s anything we could do to help her pain control.

Of course, the first thing I do is check if the patient has received IV Ketorolac and oxycodone/acetaminophen or if the nurse just jumped to IV morphine, if they have not been tried, I will ask the nurse to try them first and assess the response! If they have already been given with inadequate response, then we can do the following:

- Add scheduled high-dose oral ibuprofen, or naproxen, or acetaminophen

- Add Gabapentin

- If that remains inadequate, we add a scheduled oral opioid for a few days while escalating the Gabapentin dose

Please remember this about the use of Acetaminophen and NSAIDs:

- Don’t combine oral and IV forms of the same medication or the same class within the same severity category, for example, don’t use oral naproxen and IV ketorolac together for moderate pain, or oral acetaminophen and IV acetaminophen together for severe pain.

- Combining acetaminophen at doses higher than 2 g/day together with an NSAID isn’t more effective than an NSAID alone and might be associated with a higher risk of gastrointestinal complications! So keep that in mind!

- The total daily amount of acetaminophen shouldn’t exceed 4 g/day including all forms of acetaminophen, whether oral or IV, and the one combined with oral opioids.

More options for severe pain

There are other options to consider in severe pain cases:

- Regional block performed by surgery or anesthesia can be helpful in rib fractures or postoperative pain

- Ketamine can be considered in severe pain refractory to opioids.

- Dexamethasone can be considered where swelling and edema are suspected as a contributing factor to the pain line in disk herniation or metastatic bone pain.

- Local anesthetics like lidocaine patches are not that effective in acute severe pain management, but they can be used as an adjuvant therapy to other analgesics for superficial musculoskeletal pain.

- Muscle relaxants can be considered when muscle spasms may contribute to the patient’s acute pain

The top five antibiotics I use in the ICU

In this post, I will share when to use them, how to use them, what to monitor, and their alternatives:

(1) IV Vancomycin

- In the ICU, I reach for IV vancomycin when MRSA or resistant gram-positives are a concern — like sepsis of unknown source, ventilator pneumonia, line infections, or resistant Strep pneumo meningitis. It’s my go-to until cultures guide me otherwise, with close drug monitoring and quick de-escalation when I can.

- The initial loading dose is 20-35 mg/kg, based on actual body weight, and should not exceed 3,000 mg. So, for a 70 kg patient, it’s roughly 1.5-2 gm. Do not renally adjust for the loading dose!

- Subsequent dosing is guided by the area under the concentration-time curve to minimum inhibitory concentration ratio (AUC/MIC), not by trough-only monitoring. Fortunately, our pharmacists take care of that.

- Vancomycin can cause nephrotoxicity and agranulocytosis, which is why we monitor kidney function and CBC while on IV vancomycin.

- Vancomycin infusion reaction (previously “Red man syndrome”) occurs with IV administration. It’s a side effect, not a true allergy. Manage by slowing the infusion rate to 50% or 10 mg/min (whichever is slower). Diphenhydramine plus famotidine effectively relieves symptoms. Stop infusion only for hypotension, chest pain, dyspnea, or muscle spasms; restart at reduced rate when resolved.

- Remember that Oral vancomycin is solely used for C. diff treatment.

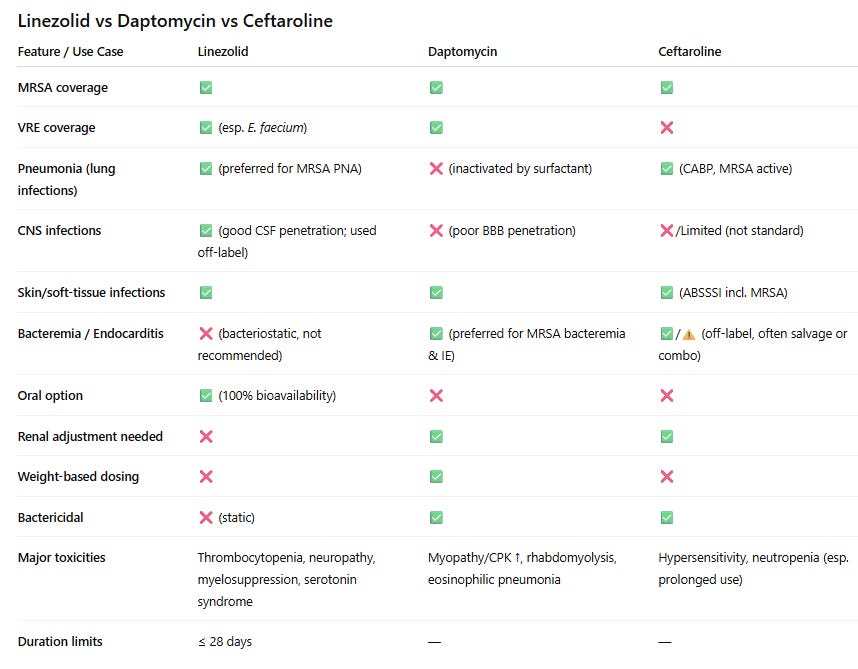

If I can’t use IV vancomycin because of allergy or toxicity, Linezolid and daptomycin are the main alternatives, and the source of infection dictates which is better to pick:

- Linezolid → preferred for lung, CNS, and skin/soft tissue infections. Easy, weight-independent dosing, 100% oral bioavailability, and safe in renal failure. But it’s bacteriostatic, not ideal for bacteremia, and can’t be combined with serotonergic drugs due to serotonin syndrome risk. Limit use to ≤28 days because of thrombocytopenia, neuropathy, and myelosuppression.

- Daptomycin → preferred for bloodstream infections, endocarditis, and other deep-seated infections (MRSA or VRE). Bactericidal, but weight-based and requires renal adjustment. Never use it in pneumonia — it’s inactivated by surfactant. Rhabdomyolysis and eosinophilic pneumonia are potential serious side effects of daptomycin.

- Ceftaroline → the only β-lactam with MRSA activity. I reach for it when linezolid or daptomycin can’t be used or when the vancomycin MIC is elevated (≥2 μg/mL). It’s useful for pneumonia and bacteremia, but requires renal dose adjustment.

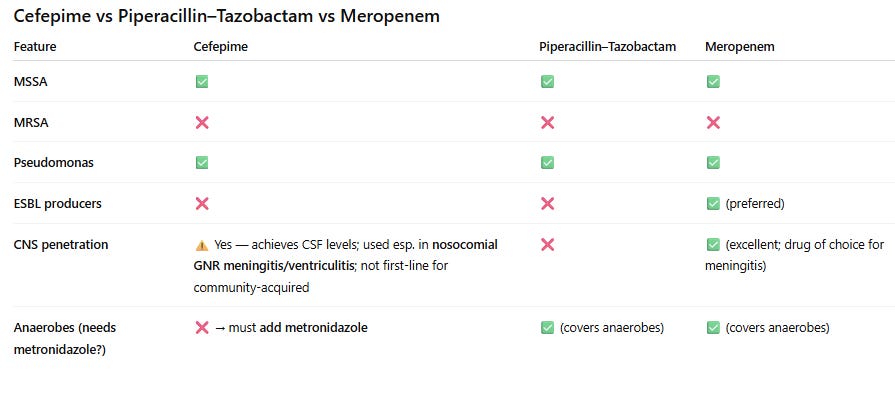

(2) Cefepime

- I reach for cefepime when broad-spectrum coverage of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria is required, such as in suspected hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia, and sepsis of unknown source.

- That’s why you see quite often the combination of vancomycin and Cefepime in initial empiric treatment for severe infection and sepsis. Vancomycin to cover for MRSA and cefepime for the rest, including Pseudomonas. Cefepime lacks anaerobic coverage, and metronidazole should be added if anaerobic coverage is required.

- Cefepime has good CNS penetration and can be used to treat CNS infections.

- Cefepime isn’t effective against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing organisms, regardless of culture and susceptibility results. Use carbapenems instead for that.

- Dosing is 1-2 gm IV every 8-12 hours and should be adjusted to renal function.

- Monitor mental status to detect cefepime neurotoxicity early. Neurotoxicity in the form of encephalopathy, confusion, hallucinations, stupor, coma, aphasia, myoclonus, seizures, and nonconvulsive status epilepticus can all happen particularly with the use of high doses in patients with renal impairment.

- If penicillin allergy is reported in the patient’s chart, ask what kind of allergy. Cefepime should only be avoided in patients who report a history of immediate hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins (such as anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria).

(3) Piperacillin/Tazobactam (Zosyn)

- In the ICU, I reach for Piperacillin/Tazobactam when broad-spectrum coverage of Gram-negativeincluding Pseudomonas, Gram-positive, and anaerobic bacteria is required (No need to add metronidazole).

- It was widely used in combination with vancomycin for the initial empiric antibiotic coverage for severe infections until it was found that this combination increases the risk of AKI! Since then, it has been largely replaced by cefepime.

- It has poor CNS penetration and shouldn’t be used for CNS infections.

- Dosing of (piperacillin and tazobactam) is dependent on the type and severity of infection being treated, and it requires renal dosing adjustment.

(4) Meropenem

- In the ICU, I reach for meropenem when ESBL-producing organisms are suspected, or when cefepime and piperacillin/tazobactam can’t be used due to a serious allergy.

- It covers Gram negatives, Gram positives, and anaerobes, and it has excellent CNS penetration, making it suitable for CNS infections.

- It has a very low cross reactivity with penicillin’s making it a great alternative in patients with serious penicillin allergy, even in those with a history of immediate hypersensitivity reactions (such as anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria).

- Among carbapenems, ertapenem lacks pseudomonal coverage.

(5) Bactrim (Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole)

- The reason I include it here because it’s the antibiotic of choice to resort to when thinking about PJP pneumonia, Nocardia, and in the treatment of stenotrophomonas maltophilia, an opportunistic gram-negative bacillus that is a common culprit in hospital-acquired infections in critically ill patients.

- Dosing is weight-based. The IV preparation of Bactrim entails the use of a large volume of dextrose solution to mix with, so watch for the risk of hyponatremia.

- Renal adjustment is required; we need to closely monitor CBC, kidney function, and electrolytes as hyperkalemia, bone marrow suppression, and hyponatremia are all potential side effects of Bactrim.

- Allergy to nonantibiotic sulfas isn’t a contraindication to use sulfa antibiotics.

Conclusion

I know there are many other important antibiotics I didn’t cover today. I wanted to keep this post focused and concise. If you’d like a bit deeper practical dive into the antibiotics we use most often in clinical practice, check out my eBook: Antibiotics in Real-Life Clinical Practice: A Pocket Guide for Residents, Hospitalists, Internists, Nurse Practitioners, and Physician Assistants. Check it out here

10 Medications You Must Master Before Your ICU Rotation

In this post, I’ll walk you through 10 medications you absolutely must master before your ICU rotation.

5 ICU hacks will save you at least two hours a day!

These 5 ICU hacks will save you at least two hours a day—and make you look sharp, confident, and in control from day one

Mechanical Ventilation Made Simple: 9 Concepts Every Non-ICU Doc Should Know

Introduction:

Mechanical ventilation doesn’t have to be intimidating. If you are a non-ICU doc who just wants to feel more prepared when your patient gets intubated, this post is for you! I’m pretty sure after this, you won’t shy away from the ventilator again.

So grab a coffee, and let’s finally make sense of mechanical ventilation. Let’s get started.

Concept (1): The respiratory cycle has two phases: expiration and inspiration.

Inspiration is an active process that requires energy. Expiration is typically passive, relying on the lungs’ natural elastic recoil.

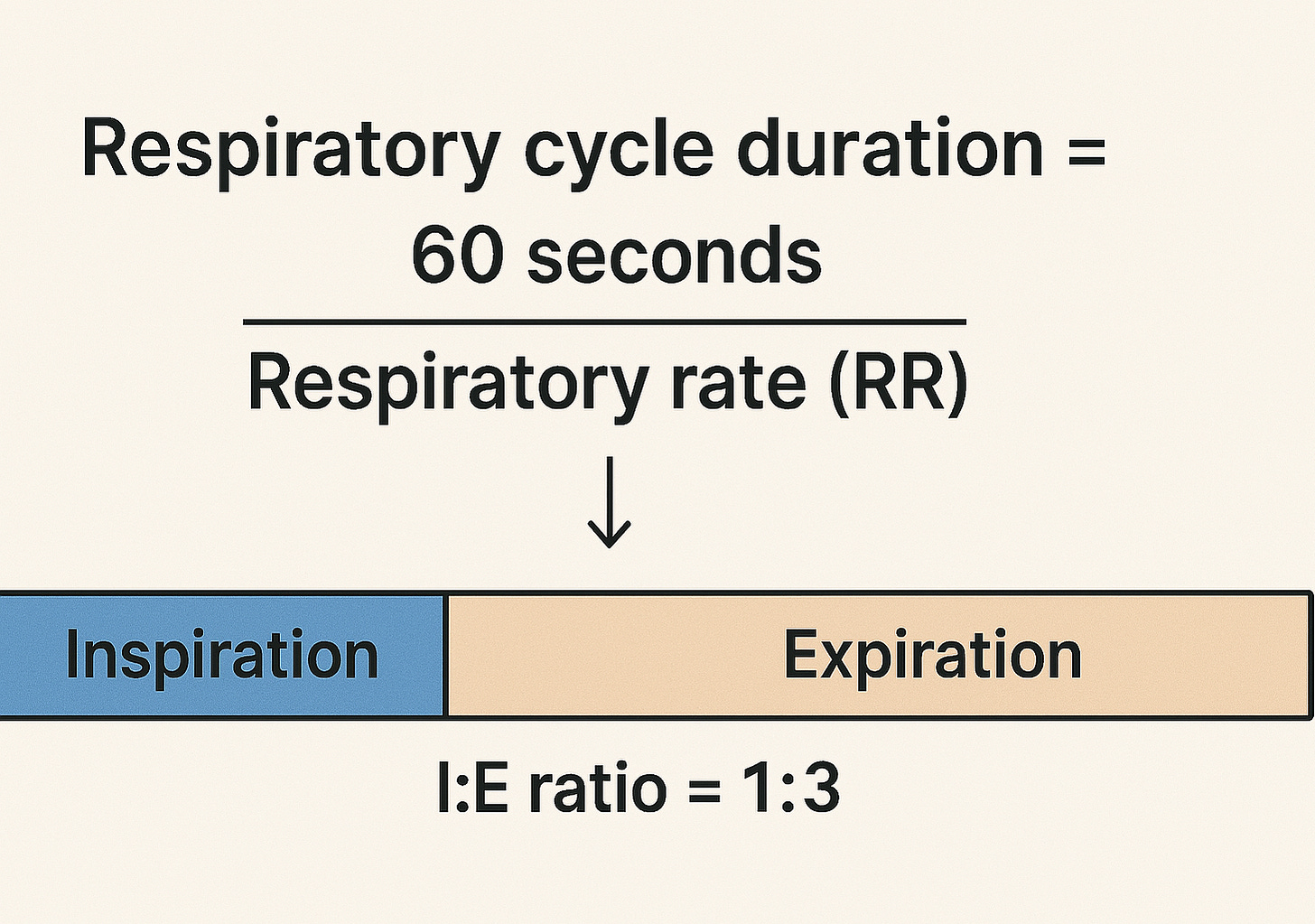

The respiratory cycle duration is calculated by dividing 60 seconds by the respiratory rate (RR). This cycle encompasses both inspiratory and expiratory time. The relationship between inspiration and expiration is not equal; physiologically, the ratio of inspiratory time to expiratory time (I:E) is typically 1:2 or 1:3, with expiration being longer than inspiration.

Example:

RR = 20 breaths/minute

The respiratory cycle duration = 60/20 = 3 seconds

Using I:E ratio of 1:3, the inspiratory time would be 0.75 seconds, and the expiratory time would be 2.25 seconds.

Concept (2): The ventilator does the heavy lifting during inspiration, but it doesn’t clock out during expiration!

As we mentioned earlier, inspiration is an active process that requires energy, so the ventilator works mainly during this active, energy-consuming phase. But that doesn’t mean the ventilator just shuts off during expiration—it continues to play a crucial role by maintaining a certain level of pressure that is called PEEP, or Positive End-Expiratory Pressure.

PEEP prevents the alveoli from collapsing at the end of expiration by holding a small amount of pressure in the lungs throughout the entire respiratory cycle, not just during the expiration phase. Think of it like a doorstop that keeps the alveoli slightly open, making the next breath easier and improving oxygenation.

Don’t be fooled by the name—PEEP isn’t just at the end of expiration. It’s present throughout the entire respiratory cycle. During expiration, it’s the only pressure applied, and during inspiration, the ventilator adds pressure on top of the PEEP to deliver the breath.

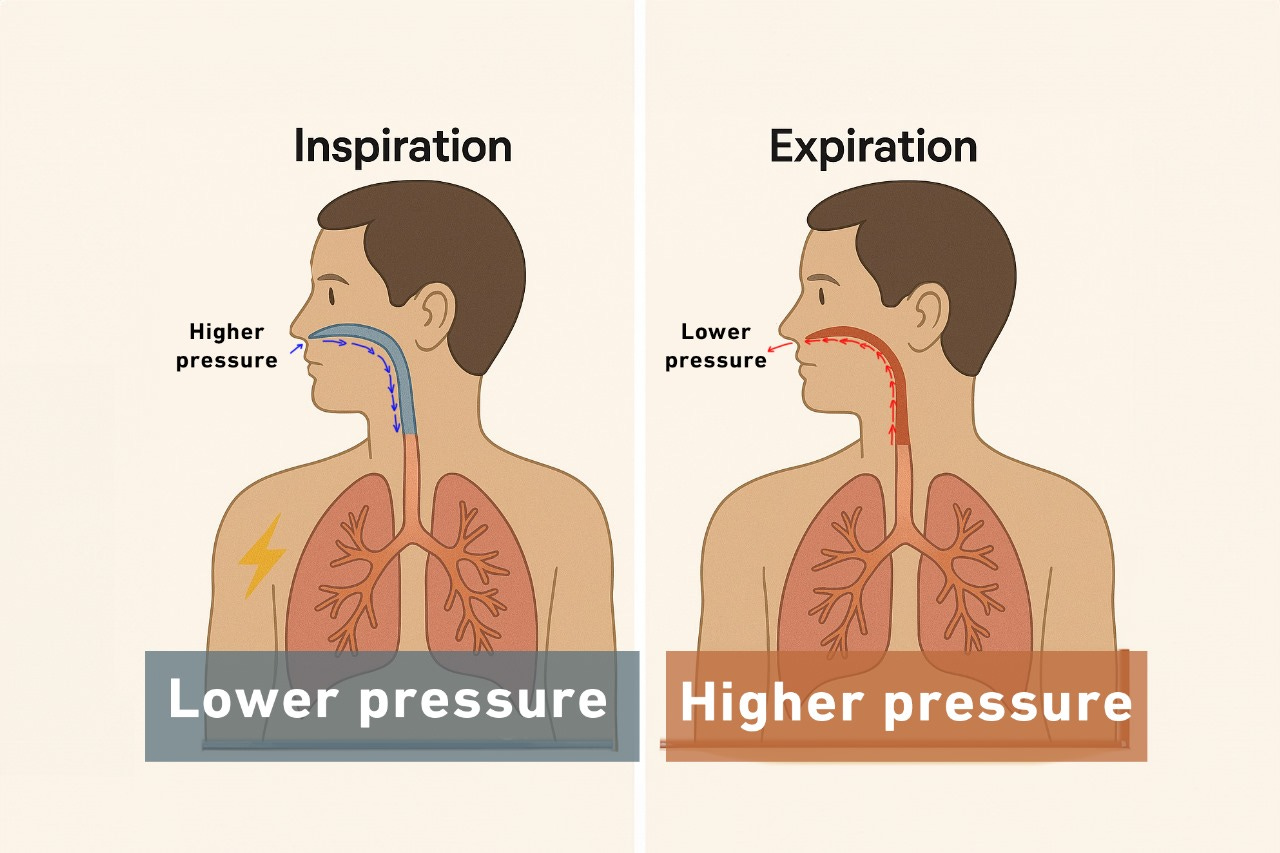

Concept (3): Air flows from higher-pressure to lower-pressure areas.

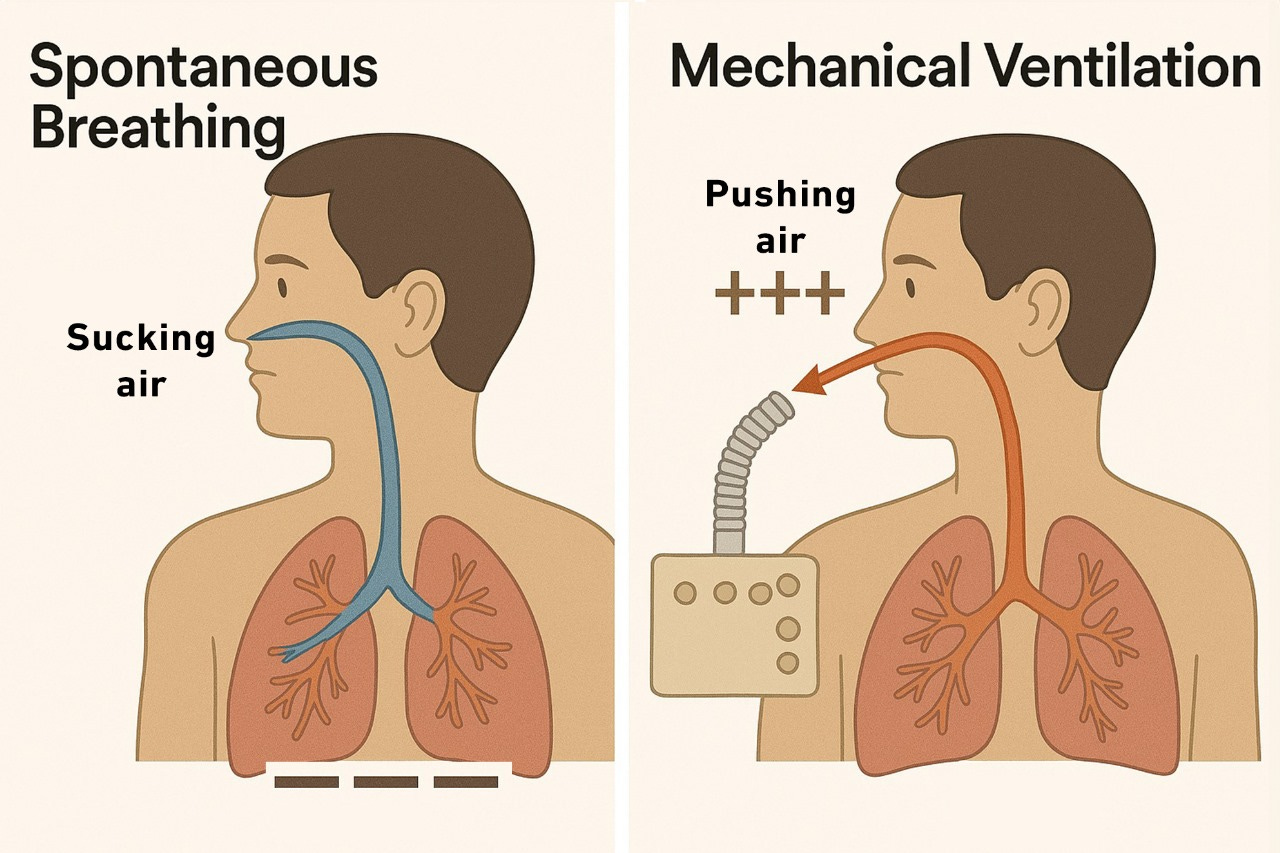

During inhalation, air enters the lungs because the pressure at the nose and mouth is higher than in the alveoli. During exhalation, the pressure in the alveoli becomes higher than at the airway opening, so air flows out. This air movement continues as long as a pressure gradient exists. In spontaneous breathing, we actively lower the pressure inside the alveoli below atmospheric pressure, creating suction and pulling air in.

In mechanical ventilation, the ventilator does the opposite: it raises the pressure at the nose and mouth above alveolar pressure to push air in. That’s why we call it a positive pressure breath

In spontaneous breath, we suck the air in; while in positive pressure breath, the ventilator pushes the air in.

Concept (4): To get air in, the ventilator has to fight three battles: the tube, the airways, and the lungs.

During mechanical ventilation, the ventilator delivers air through the endotracheal tube (ETT), down the airways, and into the alveoli. To do this, it must overcome two main types of resistance:

- The airway resistance (from the ETT and conducting airways).

- The elastic resistance (from the alveoli and lung tissue).

The airway resistance

This resistance is primarily due to their narrow lumens and flow dynamics. The pressure required to overcome this kind of resistance is called Resistive pressure, and it is calculated by multiplying the flow by the airway resistance.

Resistive Pressure = Flow (F) × Resistance (R)

The elastic resistance

The alveoli are evaluated based on their compliance—their ability to stretch and accommodate volume. The pressure required to overcome alveolar and lung tissue stiffness is called Elastic pressure, and it’s calculated by dividing volume by compliance.

Elastic pressure = Tidal volume (TV) ÷ Compliance (C)

In mechanical ventilation, the volume here simply represents TV, and the elastic pressure represents the alveolar pressure, so the equation can be rewritten as:

Alveolar pressure = TV/C

Therefore, for a full breath to be delivered, the ventilator must generate enough total pressure to overcome both the resistive and elastic or alveolar pressures. In mechanical ventilation, this pressure is called the peak inspiratory pressure (PIP).

Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) = Resistive pressure + Elastic pressure.

Which can be rewritten as:

PIP = (F x Airway resistance) + (TV/C)

Based on this equation:

- PIP is proportionally related to Flow, airway resistance, and TV.

- Inversely related to compliance.

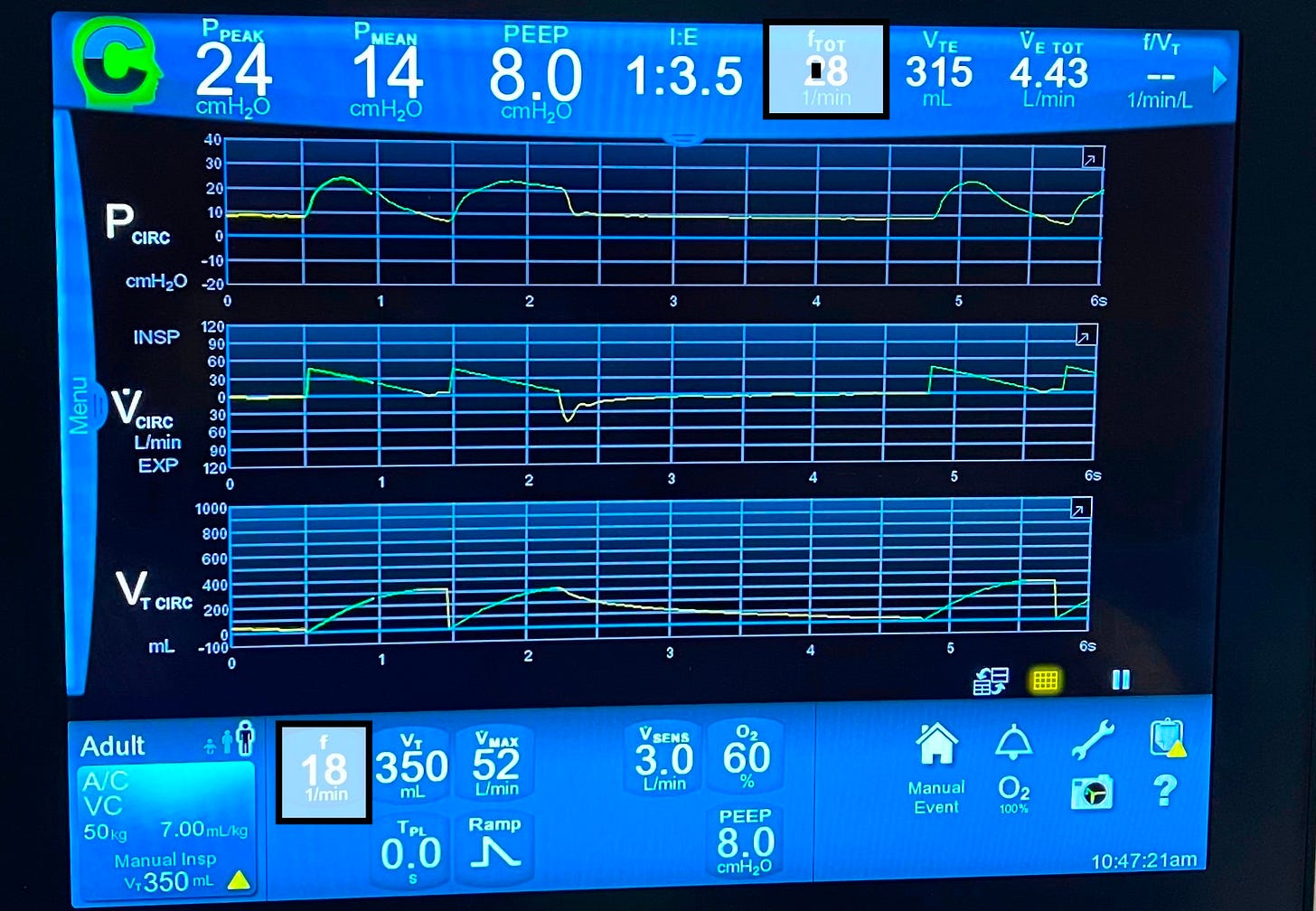

Take a peek at this ventilator screen: The PIP is 20 cmH2O, the flow rate is 44 L/min, and the tidal volume is 500 mL.

- Guess what will happen to the PIP if I increase the flow or the tidal volume? Based on the equation, the peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) will increase.

- What will happen to the PIP if the patient bites the endotracheal tube or develops bronchospasm, both of which increase airway resistance? Again, you’ll also see a rise in PIP.

- Let’s say the patient develops pulmonary edema and bilateral pleural effusion. What would happen to the PIP in such a case? Pulmonary edema and bilateral pleural effusion reduce the alveoli’s ability to accommodate tidal volume (reduce their stretchability and compliance). PIP is inversely related to compliance; now the ventilator has to push harder to get the breath in, which means higher PIP is required!

Concept (5): Plateau Pressure: Your Window into Lung Compliance

Let’s imagine a moment when the flow drops to zero— this occurs briefly at the end of inspiration, just before expiration begins, and again at the end of expiration, just before the next inspiration starts. These are the transition points between phases of the respiratory cycle when there’s no airflow because the pressures between the airway and alveoli are equal.

Guess what happens to the PIP when the flow drops to zero? Let’s go back to our equation:

PIP = (Flow×Resistance) + (Tidal Volume/Compliance)

If the flow drops to zero, the resistive component disappears, and the equation simplifies to:

PIP = TV/Compliance = Alveolar Pressure.

This means when the flow is zero, the PIP is equal to the alveolar pressure, and this makes sense as pressure gradient means flow, and the absence of the gradient means no flow.

In mechanical ventilation, the pressure measured at the end of inspiration when the flow ceases is known as the Plateau pressure. Plateau pressure provides great insight into lung compliance. The lower the plateau pressure, the more compliant, stretchable, and less stiff the lung is, and vice versa!

How do we measure the plateau pressure? Plateau pressure is measured using the inspiratory pause or hold maneuver. In clinical practice, we aim for a PIP < 35 cmH2O and a plateau pressure of < 30 cmH2O.

How about the opposite? I mean the pressure measured at the end of expiration and before the inspiration valve opens? What do you think the alveolar pressure should be in such a case? We mentioned earlier that PEEP is the only pressure the ventilator provides during expiration, which means the expiratory flow will continue until the alveolar pressure drops from the maximum value at the end of inspiration (plateau pressure) down to the PEEP value, when the flow ceases. So normally, the alveolar pressure measured at the end of expiration when there is no flow must equal PEEP.

To confirm that, we perform what we call the expiratory pause maneuver. This maneuver allows us to check for any gas trapping and autoPEEP.

Concept (6): The ventilator can’t think for itself—it needs our guidance

For the ventilator to function properly, we have to give it five instructions:

- When to start the breath.

- How to deliver the breath.

- When to terminate the breath.

- How much oxygen to give?

- How much PEEP to give?

1. When to start the breath or inspiration?

The ventilator listens to the patient to detect the patient’s inspiratory effort. It will pick up any inspiratory effort as a sign that the patient is trying to breathe, and it will assist the patient with that breath! This is known as a patient’s triggered breath or, as we call it in mechanical ventilation, an Assist breath or “A” breath.

But what happens if the ventilator doesn’t detect any patient trigger? Let’s say the patient is paralyzed or brain-dead.

In this case, the ventilator has a built-in safety mechanism: it will deliver a breath if no patient’s trigger is detected for a specific time! This is called a backup breath or, as we call it in mechanical ventilation, a Control breath or “C” breath.

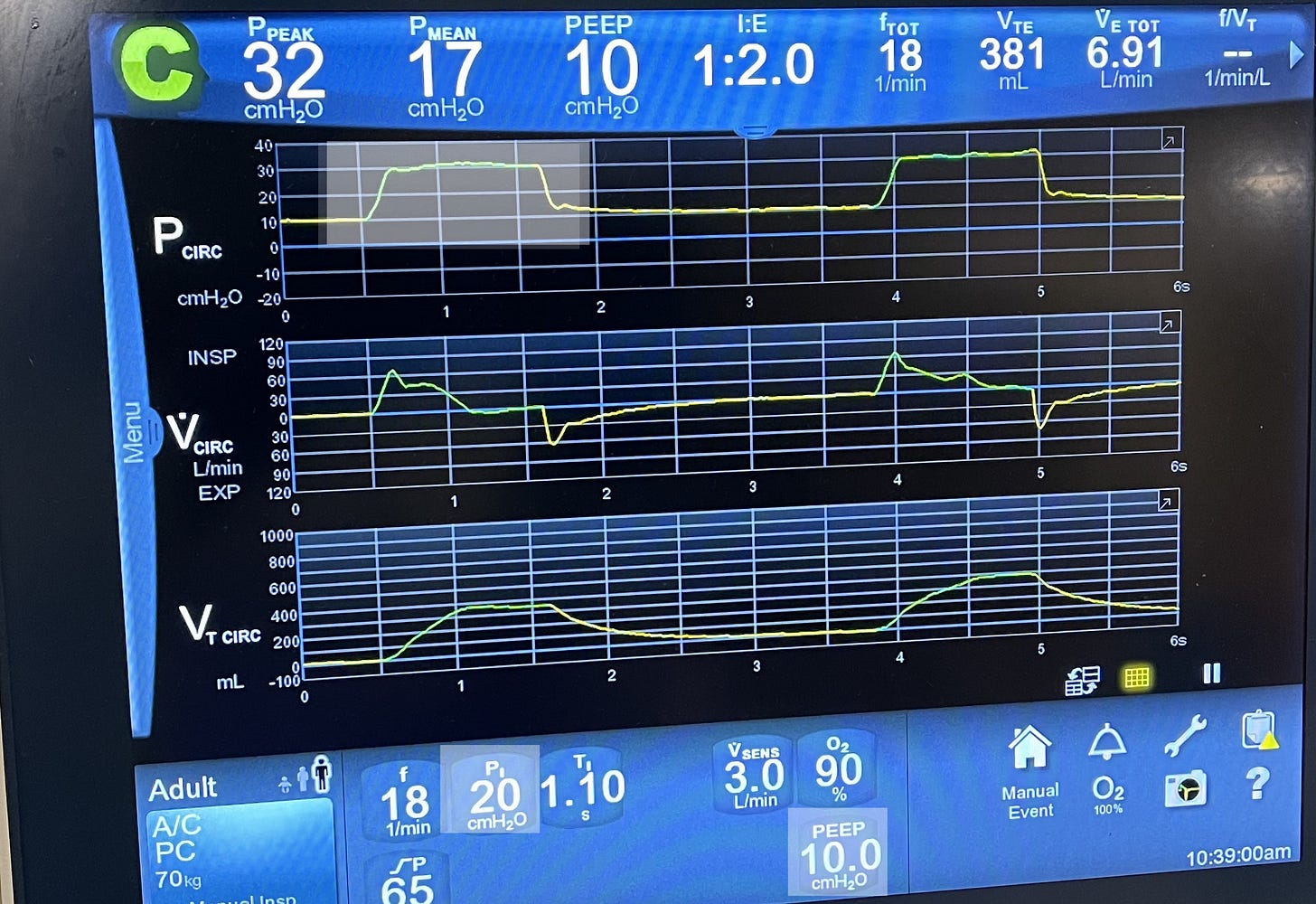

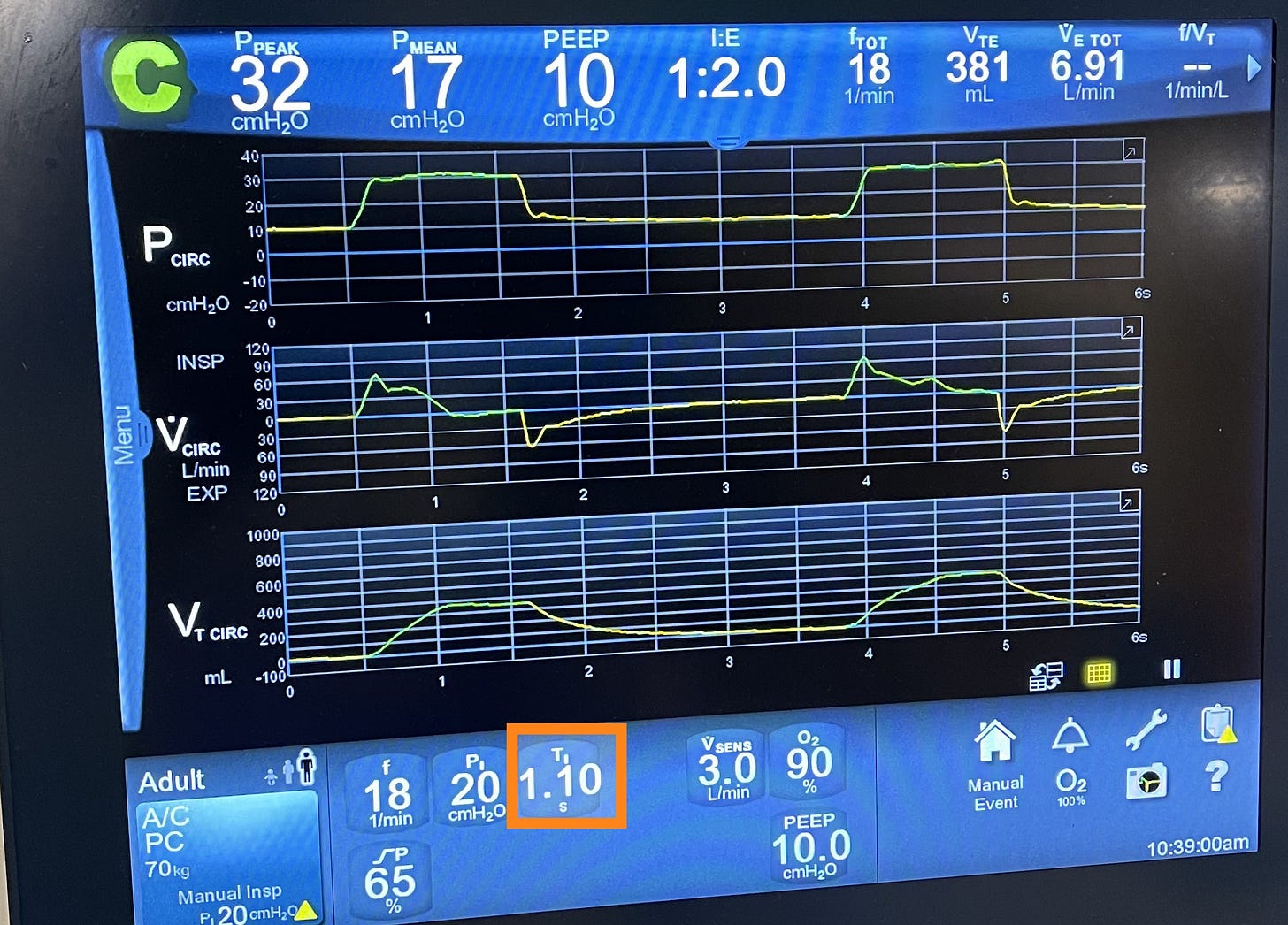

Take a look at these two ventilator screens. The breath on picture A is a controlled or backup breath labeled as C breath, and the breath on picture B is an assist breath triggered by the patient and assisted by the ventilator.

But what decides how long the ventilator should wait before delivering a backup breath? This timing is based on the set respiratory rate (RR), which is known as the backup rate. The backup rate is the minimum number of breaths/minute the patient receives, even if they make no effort to breathe. The ventilator will listen to the patient for a period equal to [60 sec/backup RR] before delivering the backup breath.

Example: If the backup rate is set to 15 breaths per minute, the ventilator waits up to 4 seconds (60 ÷ 15), and if no patient’s trigger is detected, a backup breath will be delivered!

The actual RR is either equal to or higher than the backup rate, but never lower! This is important when trying to adjust the backup RR. Let’s say the backup rate is 14 and the patient is breathing at 20 breaths/min; there is no point here if you increase the backup rate to 16 because the actual RR is already higher!

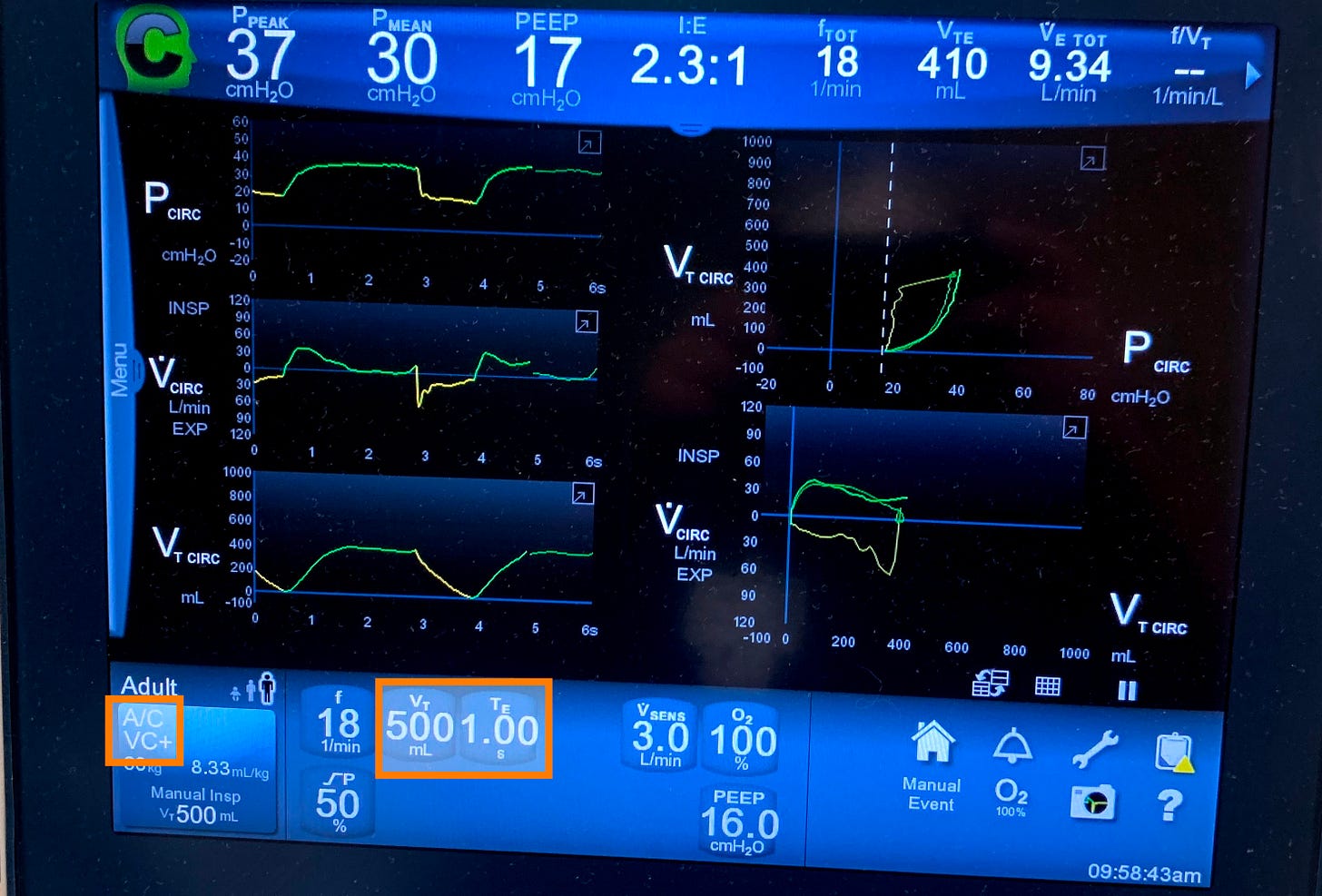

Take a look at this ventilator screen, see the set backup rate at 18 while the actual RR on the top is 28. Increasing the backup rate will not have any impact unless it becomes higher than the actual RR.

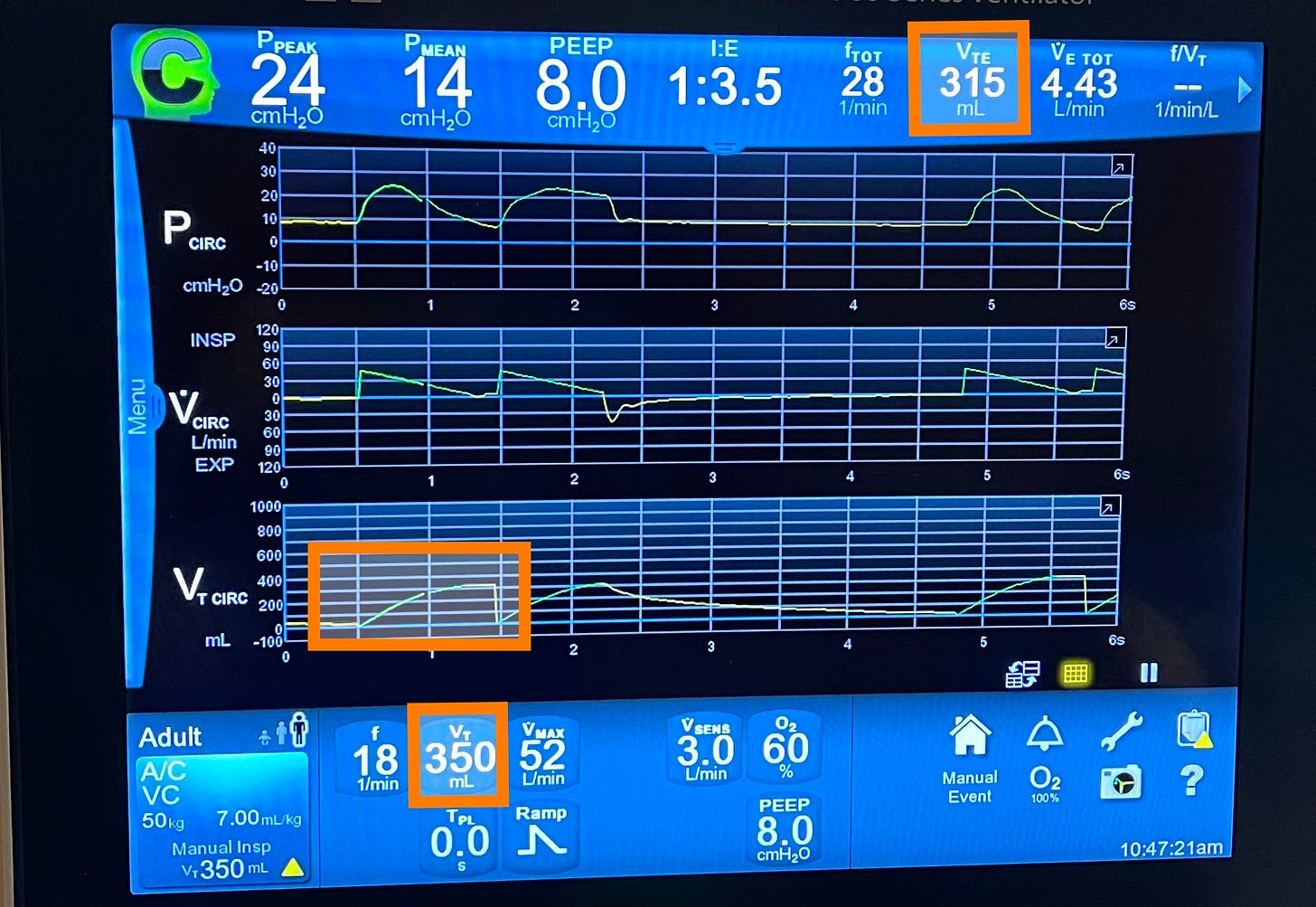

The values at the bottom of the picture are the set values that we provide, while those at the top are the actual live values! The ventilator tries to fulfill the set values or close to them (See the set TV is 500, but the actual one is 524).

Back to the trigger, how does the ventilator detect the patient’s trigger?

In spontaneous breathing, the patient generates negative pressure in the alveoli, which creates a suction effect that pulls air in. When the patient is intubated and connected to a ventilator, this same effort draws air through the circuit, and that’s how the ventilator knows it’s time to assist.

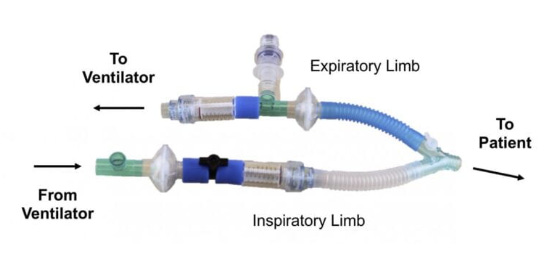

Take a look at the ventilator circuit picture below: you’ll notice two limbs connected to the endotracheal tube (ETT)—the inspiratory limb, which carries air from the ventilator to the patient (often passing through a humidifier), and the expiratory limb, which returns air from the patient back to the machine.

When the patient is not making any effort, air flows equally through both limbs. When the patient initiates a breath, he pulls some air from the inspiratory limb into his lungs, reducing the flow returning through the expiratory limb. The ventilator senses this imbalance and interprets it as an inspiratory effort and will go ahead and assist the patient with that breath. This is called a flow trigger.

Alternatively, the ventilator can detect a drop in airway pressure (caused by the patient’s inspiratory effort) and use that as a trigger. This is called a pressure trigger.

🔁 To summarize: the ventilator can recognize a patient’s attempt to breathe in two ways:

- Flow Triggering – by sensing a drop in flow through the expiratory limb.

- Pressure Triggering – by sensing a drop in airway pressure.

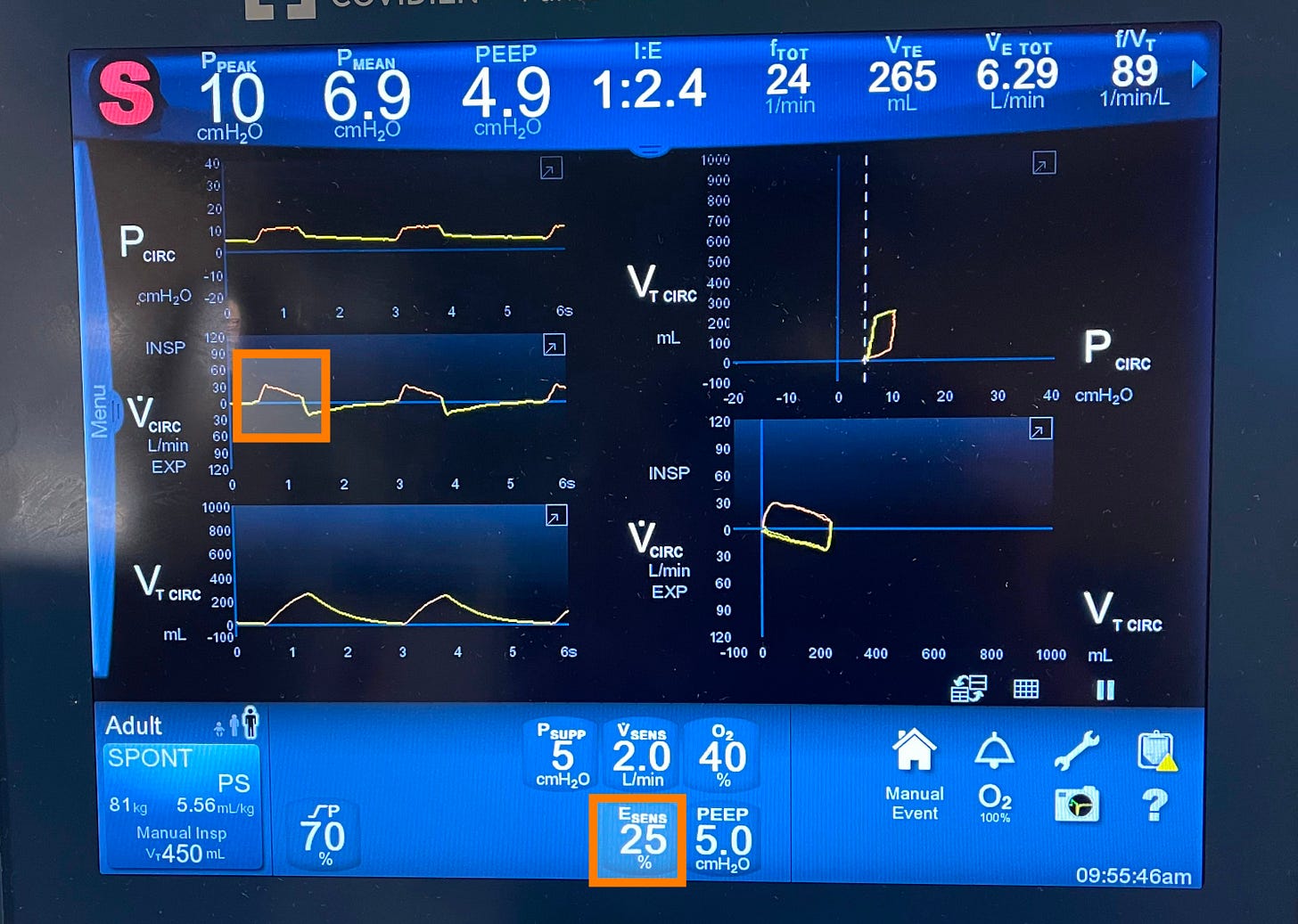

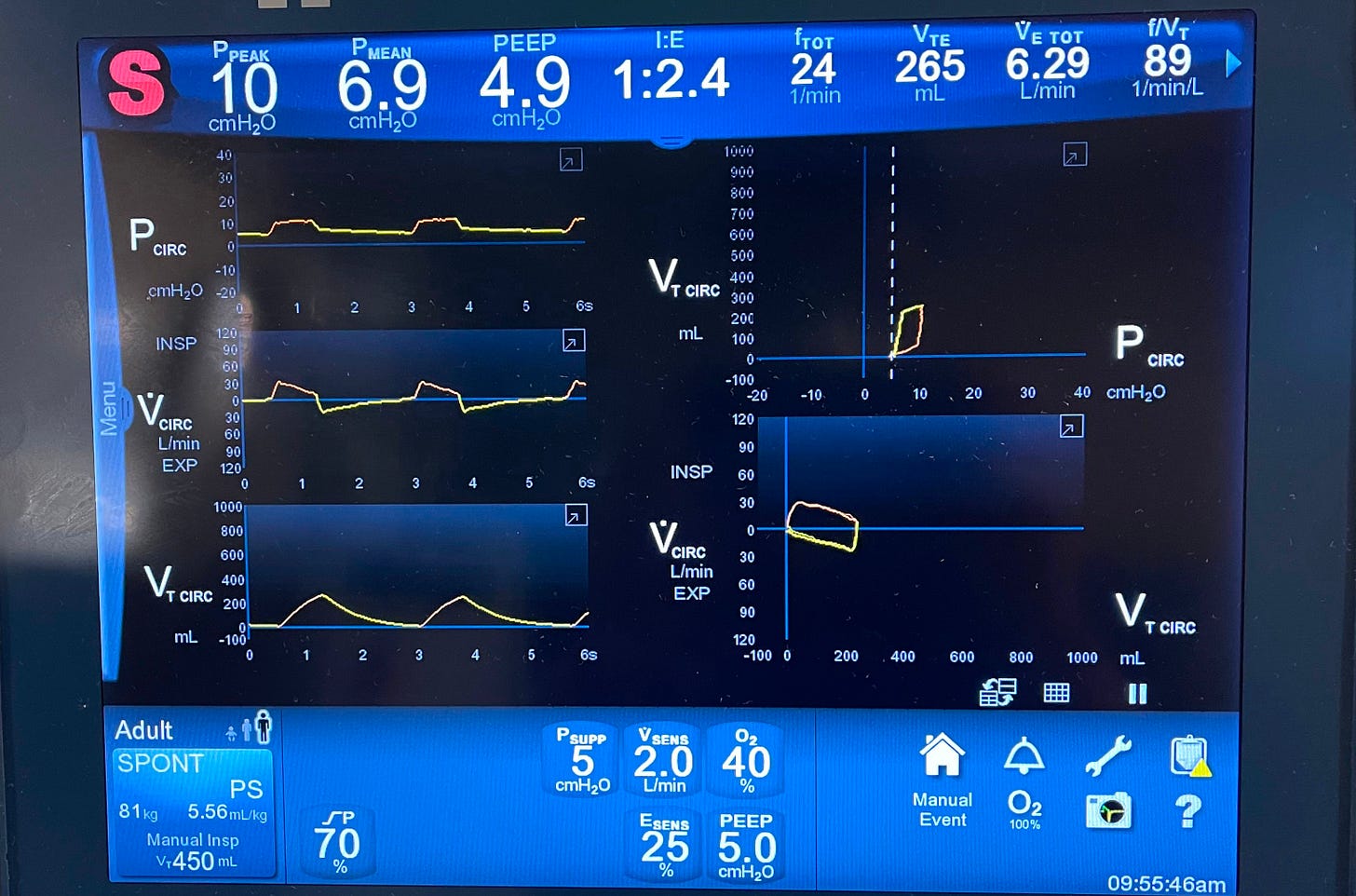

Take a look at these two screenshots of two ventilators:

- On Picture A, Psens shows the pressure trigger. It’s set at 2 cm H₂O, meaning the patient must reduce his airway pressure by at least 2 cm H₂O to trigger a breath. We usually set this between 2 and 3 cm H₂O.

- On picture B, Vsens represents the flow trigger, set at 3 L/min. This means the patient must draw in at least 3 L/min (approximately 50 mL/sec) for the ventilator to deliver a breath.

Whether using a flow trigger or a pressure trigger makes no clinical difference—neither offers a clear advantage over the other.

2. How should the ventilator deliver this breath?

In mechanical ventilation, we refer to the way of delivering the breath as the “target.” Although the term can be confusing, the concept is straightforward—just give me your full attention!

Let’s bring back our lovely equation again:

PIP = (F x R) + (TV/C).

Which can be rewritten as: PIP = (F x R) + Alveolar pressure. Which can be rearranged into: F = (PIP – Alveolar pressure) / Resistance.

In mechanical ventilation, we can directly set the flow rate and the peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) on the ventilator. However, alveolar pressure and airway resistance are not directly settable—they’re influenced by the patient’s lung mechanics and underlying condition.

Based on the equation, mathematically, for the pressure–flow relationship to hold true, we can only set one variable—either the pressure or the flow, but not both. That’s because one must remain flexible to allow the other to stay fixed. If we fix both, the equation wouldn’t hold under changing patient conditions.

This will leave us with one of two options to deliver the breath:

- You can either set the flow and let the pressure adjust, which is called the flow target.

- Set the pressure and let the flow adjust, which is called the pressure target.

In flow-targeted ventilation, we start by setting the desired flow rate. From there, we have two main subtypes based on how that flow is delivered:

- We can ask the ventilator to keep the flow rate fixed throughout the inspiratory phase, which results in a square or rectangular flow vs time curve.

- Or we can ask the ventilator to give the set flow rate only at the beginning of the breath, and let it progressively drop or decelerate throughout the rest of the inspiratory phase! This results in a decelerating ramp flow vs time curve.

In clinical practice, we primarily use the decelerating ramp flow, it generally results in a lower peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) compared to the constant (square) flow pattern.

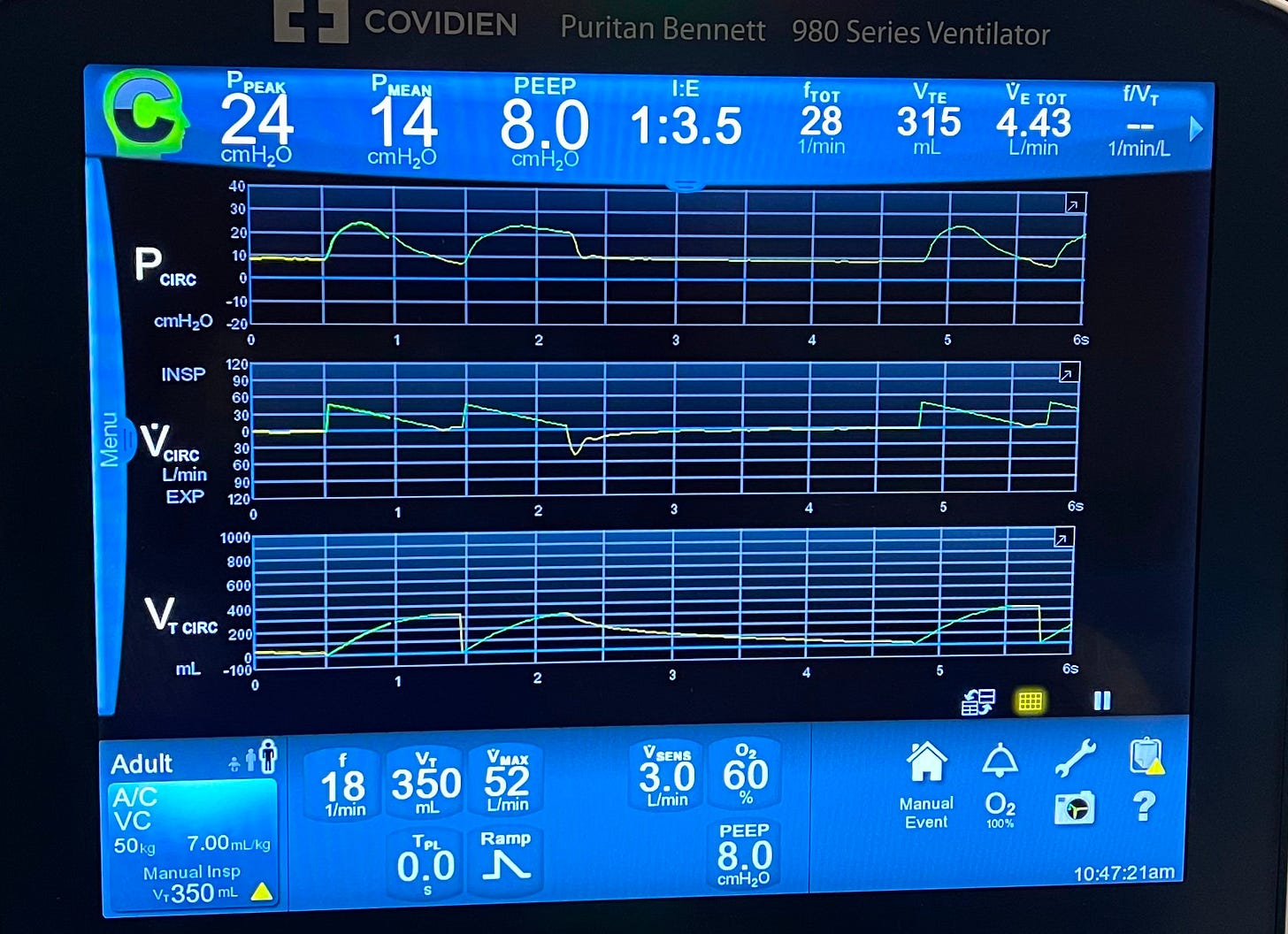

Take a look at this flow target on this ventilator screen and notice:

- The green curve shows the decelerating ramp flow pattern.

- On the info panel, the flow target is set at Vmax: 44 L/min with the ramp type set to decelerating.

How about the pressure target ventilation?

Here, we tell the ventilator to apply a fixed amount of pressure on top of the PEEP throughout the inspiratory phase until the breath is delivered.

What do you think the flow pattern will be in the pressure target? To maintain a fixed pressure throughout the inspiratory phase, the flow must progressively decrease to keep this equation valid, “F = (PIP – Alveolar pressure) / Resistance”. Of course, as long as the resistance is constant. That’s why the flow vs time curve is always a decelerating ramp curve in pressure target modes.

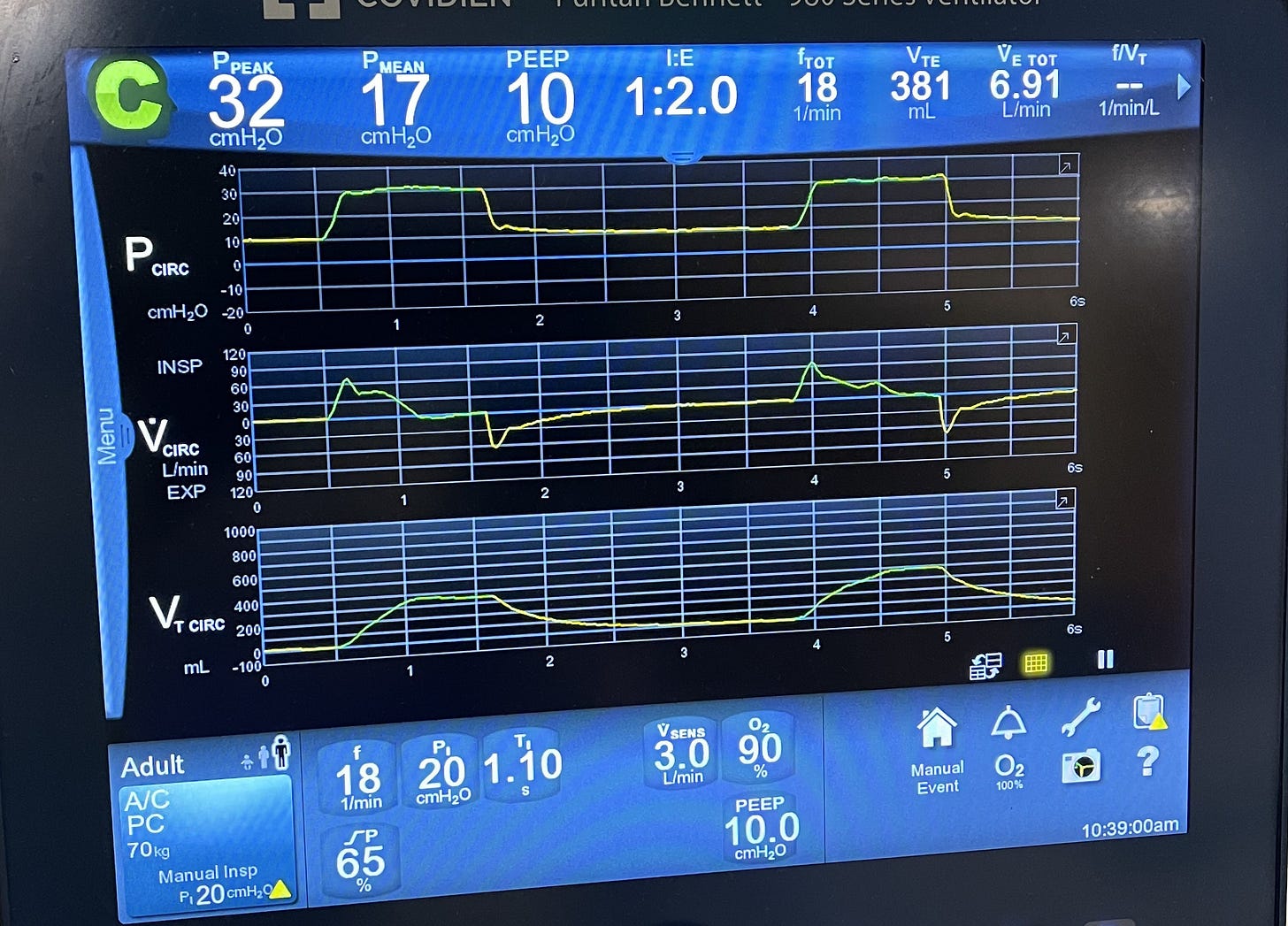

Take a look at this ventilator screen, see the fixed pressure here. The ventilator adds 20 cmH2O on top of PEEP of 10 and keeps it there during the whole inspiration. The flow curve is a decelerating ramp curve.

What do you think will happen to the flow rate if we set the inspiratory pressure (Pi) at 30 cmH2O instead of 20?

If we increase the inspiratory pressure from 20 to 30 cmH₂O, the flow rate will increase; so the higher the set pressure, the greater the initial flow the ventilator delivers.

3. When should the ventilator stop delivering the breath (Cycle)?

This is known as the ‘cycle’ in mechanical ventilation. There are three main mechanisms to determine when the ventilator stops inspiration and switches to expiration. These are known as cycling mechanisms:

Volume-Cycled Ventilation:

In volume-cycled breaths, the ventilator ends inspiration once the preset tidal volume (TV) is delivered.

🔍 Look at the ventilator screen below and see the volume vs time curve. Once it reaches the desired TV, it will switch from green color, which represents inspiration, to yellow color, which represents expiration. Also, look at the top panel and see that the actual TV was 315! In reality, the ventilator doesn’t always fulfill the exact set TV, but it will be close to that!

What do you think will happen to the inspiratory time if we increase the TV here? Of course, it will increase; the larger the volume, the longer it takes to deliver it. The opposite is true.

Time-Cycled Ventilation:

In time-cycled breaths, the ventilator switches to expiration after a preset inspiratory time has elapsed, regardless of the volume delivered.

🔍 Check the ventilator screen for the set inspiratory time and see that the green line in all the curves switches to yellow after the set inspiratory time.

What do you think the TV will be if we shorten the insp time? It will be smaller as we spending less time delivering the breath, the opposit is true.

Flow-Cycled Ventilation:

In flow-cycled breaths—used primarily in pressure support mode—the ventilator ends inspiration when inspiratory flow drops to a preset percentage of peak inspiratory flow.

🔍 Look at this screen and see the “Esens” or expiratory sensitivity setting (commonly set at 25%)—the breath ends when flow falls to 25% of its peak during inspiration.

What will happen to the TV if we set ESens at 50% instead of 25%? It will be smaller as we are having a shorter inspiratory time! The opposite is true.

4. How much FiO₂ and how much PEEP? These two are oxygenation parameters, and we’ll discuss them later in this post.

Concept (7): Every Mode Is a Recipe: You Just Change the Ingredients

At the heart of mechanical ventilation are three fundamental modes:

🔹 Volume Control.

🔹 Pressure Control.

🔹 Pressure Support.

Every other mode you’ll encounter is either a hybrid or a modification of these three.

To make sense of any mode, just break it down into the three key ingredients we just explained:

🟢 Trigger – What starts the breath?

🟡 Target – How to deliver the breath?

🔴 Cycle – What ends the breath?

Before I go further!

If you’re finding this helpful, you’re going to love my full mechanical ventilation course. It covers everything we’re walking through in this video—from triggers, targets, and cycling to all the core modes—plus much more, like: Troubleshooting PIP, Rise time, Mean airway pressure, Auto-PEEP and gas trapping, Assessing weaning readiness, and how to do a proper weaning trial.

It’s designed to walk you through mechanical ventilation step-by-step, in a way that’s clear, visual, and practical.

If you’re ready to truly master the vent and feel confident at the bedside, check out the course.

Volume control or VC mode

- Trigger: VC mode typically uses assist/control (A/C) triggering. As we explained earlier, the ventilator delivers a breath either when the patient initiates one or, if the patient doesn’t, the ventilator will trigger a breath based on the set backup respiratory rate.

- Target: VC mode is flow-targeted, commonly using a decelerating ramp flow pattern.

- Cycle: VC is volume-cycled, meaning the breath ends once the preset tidal volume (TV) has been delivered.

So when ordering VC mode, in addition to the FiO2 and PEEP values, we need to provide the respiratory therapist with the following values:

- The backup RR.

- The TV.

- The Flow curve: square or decelerating.

- The Peak flow rate.

In most cases, RT will, by default, pick a decelerating ramp flow curve and set the peak flow rate; a reasonable starting peak flow rate is between 40-60 L/min.

Take a look at this VC mode screenshot,

Pressure Control (PC) Mode

- Trigger: Like VC mode, PC mode uses assist/control (A/C) triggering, meaning the breath can be triggered either by the patient’s effort or by the ventilator’s set backup respiratory rate if no spontaneous inspiratory effort is detected.

- Target: As the name suggests, PC mode is pressure-targeted. The ventilator delivers a breath by applying a set inspiratory pressure above the PEEP, and adjusts flow as needed to maintain that pressure throughout inspiration.

- Cycle: PC mode is time-cycled—the breath ends when the set inspiratory time has elapsed, regardless of how much volume was delivered.

When ordering PC mode, in addition to the FiO2 and PEEP values, we need to provide the respiratory therapist with the following values:

- Back up RR.

- Pi or inspiratory pressure, this is the pressure that will be added on top of the PEEP during inspiration.

- Ti or inspiratory time, this is the time the inspiratory pressure will be applied for.

Pressure support (PS) mode

- Trigger: This mode is patient-triggered only—there’s no backup respiratory rate. That’s why it’s suitable only for awake, spontaneously breathing patients, typically during the weaning phase of mechanical ventilation.

- Target: PS mode is pressure-targeted, similar to PC mode. The ventilator delivers a breath by applying a set inspiratory pressure above PEEP to assist the patient’s spontaneous effort.

- Cycle: PS mode is flow-cycled. The breath ends when the inspiratory flow decreases to a preset threshold, usually 25% of the peak inspiratory flow.

When ordering PS mode, in addition to FiO2 and PEEP values, we provide the respiratory therapist with the following values:

- Inspiratory pressure. In this mode, it’s called Pressure support.

- The flow cycle percentage is typically 25%.

There’s no backup RR because it only uses the patient’s trigger.

Concept (8): No Mode is perfect!

Each mode has its advantages and limitations.

Key Differences in Volume, Pressure, and Support Modes:

- Volume Control (VC):

You’re guaranteed a set tidal volume, but there’s no cap on peak inspiratory pressure (PIP)—it can rise significantly if the lungs are stiff or airways are tight. - Pressure Control (PC):

The PIP is controlled and capped at the set level, but the tidal volume will vary based on the patient’s lung compliance and airway resistance. - Pressure Support (PS):

Similar to PC, PIP is limited by the set pressure support level, but tidal volume is not fixed. This mode is patient-triggered and commonly used for weaning.

How about if I take the good stuff from each mode? If I take the set tidal volume from VC mode and the controlled inspiratory pressure from PC mode? Well—that’s exactly how PRVC (Pressure-Regulated Volume Control) was born!

In PRVC, you set the tidal volume you want delivered along with the maximum pressure limit—this acts as a safety cap, not the actual pressure used in each breath.

Here’s how it works:

The ventilator adjusts the inspiratory pressure breath-to-breath to deliver the set tidal volume, while keeping the pressure as low as possible.

If the patient’s lung compliance worsens (like in ARDS), the ventilator will increase the pressure trying to maintain the tidal volume—but only up to the set pressure limit.

If compliance improves, the ventilator will lower the pressure accordingly.

If the pressure needed to deliver the tidal volume exceeds the set limit, the ventilator won’t go higher—it will under-deliver the volume and often trigger a low tidal volume alarm. That’s why choosing a reasonable pressure limit is important, especially in patients with stiff lungs.

Some ventilators also require or allow you to set an inspiratory time (Ti) in PRVC mode. If used, Ti helps shape how long the inspiratory pressure is applied. A longer Ti can help improve alveolar recruitment and oxygenation in patients with stiff lungs, while a shorter Ti may be needed in patients with obstructive lung disease to prevent air trapping.

So, in addition to FiO₂ and PEEP, the following parameters are typically set in PRVC:

- Backup respiratory rate, since it uses an A/C trigger.

- Tidal volume, because it’s volume-cycled.

- Maximum pressure limit, as a safety guard to prevent barotrauma.

- Inspiratory time (Ti), on some vents, to control the duration of pressure delivery and fine-tune I:E ratio.

Take a look at this ventilator screen (notice this particular ventilator manufacturer calls PRVC mode VC+)

SIMV (Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation) is essentially a blend of VC or PC with pressure support. I won’t dive deeper into SIMV here, as I rarely use it in practice today, and there’s no strong clinical justification for choosing it over other modes.

Current evidence does not support the superiority of SIMV, VC, PC, or PRVC over one another in terms of clinical outcomes for patients with acute respiratory failure or other critical care conditions.

The choice of ventilation mode should always be individualized, based on the patient’s clinical status, lung mechanics, and response to therapy! I like PRVC as it may offer advantages in terms of lower peak inspiratory pressures and more stable gas exchange, making it a reasonable first choice among the three modes.

Concept (9): Tuning the Vent (Oxygenation vs. Ventilation)

When managing a ventilated patient, it’s crucial to understand what you’re trying to fix—are you trying to improve oxygenation or ventilation?

These are two distinct goals, and each is managed by adjusting different ventilator settings:

- To improve oxygenation, we focus on increasing FiO₂ and PEEP.

- To improve ventilation ( CO2 removal), we adjust the tidal volume (TV) and respiratory rate (RR).

Knowing which “knob to turn” allows you to make targeted, effective changes based on your patient’s needs—without overcomplicating things.

Hypoxia

I typically start with an FiO₂ of 100% and a PEEP of 10 cmH₂O. From there, I aim to wean the FiO₂ as quickly as possible, targeting ≤60% to minimize the risk of oxygen toxicity.

I avoid reducing PEEP until FiO₂ is down to 60% or less. If I can’t lower FiO₂ safely, I’ll consider increasing PEEP—usually in increments of 2–4 cmH₂O—to improve oxygenation. But keep in mind: raising PEEP will also increase peak inspiratory pressure (PIP).

For refractory hypoxemia, there are additional advanced strategies—such as recruitment maneuvers, paralytics, inhaled pulmonary vasodilators, and ECMO—which are beyond the scope of this video and should be managed by an intensivist.

And don’t forget: in patients with ARDS, early prone positioning is a key intervention that can significantly improve oxygenation.

Ventilation

When it comes to improving ventilation (i.e., CO₂ removal), the two main variables we adjust are the tidal volume (TV) and the respiratory rate (RR).

✅ Key Principles:

- Always use predicted body weight (PBW)—not actual body weight—to calculate tidal volume.

- In ARDS, we aim for a lung-protective strategy:

➤ 6 mL/kg PBW - In most other conditions, a range of 6–8 mL/kg PBW is acceptable.

- In ARDS, we aim for a lung-protective strategy:

- If more ventilation is needed, it’s generally safer to increase the RR rather than the tidal volume to reduce the risk of volutrauma, but remember that the higher the RR, the shorter the respiratory cycle, which affects the I:E ratio.

🛠 How Tidal Volume Is Set (or Adjusted) in Different Modes:

- In VC and PRVC modes, the tidal volume is set directly and can be easily adjusted.

- In PC and PS modes, tidal volume is not set—instead, it depends on:

- The pressure gradient between PIP and PEEP.

- The inspiratory time.

📈 In Pressure Control (PC) Mode:

To increase tidal volume:

- Increase the inspiratory pressure (PIP).

- Decrease the PEEP (carefully, as this may affect oxygenation).

- Or do both to widen the pressure gradient.

- Increase inspiratory time (Ti) to allow more time for lung filling.

📈 In Pressure Support (PS) Mode:

It’s the same concept, just different terminology:

- The “pressure support” setting is analogous to the “inspiratory pressure” in PC mode.

- Inspiratory time is not directly set, but can be adjusted by modifying the flow cycle threshold:

- Lowering the flow cycle percentage prolongs inspiratory time.

- Raising it shortens inspiratory time.

Let’s wrap it up here! I hope this post gave you a strong foundation in mechanical ventilation and helped make things clearer and more practical for your clinical work.

If you’re ready to take it to the next level and truly master topics like PIP, mean airway pressure, rise time, gas trapping, and auto-PEEP, inverse ratio ventilation, as well as how to assess weaning readiness and perform a proper weaning trial—then check out my full mechanical ventilation course here. It’s packed with real-world explanations, visuals, and tips I’ve gathered over years of hospitalist practice. You’ll find the link below—I’d love to have you in the course!

How to Measure Blood Pressure Correctly At Home

Introduction

There are three key ingredients to ensure accurate BP measurement at home:

- Choosing the right time.

- Mastering the right technique.

- Using the right device.

Choosing the right time.

The short answer: There’s no single perfect time—but there are best practices.

You can check your blood pressure at different times throughout the day, and I often encourage my patients to do so. However, for the most accurate reading, avoiding certain activities beforehand is crucial.

Tips for Accurate Blood Pressure Readings (Per ACC & AHA Guidelines):

✅ Avoid caffeine, alcohol, exercise, and smoking for at least 30 minutes before measuring.

✅ Sit quietly for 5 minutes before taking your reading—keep your feet flat on the floor and your back supported.

✅ Empty your bladder beforehand, as a full bladder can raise your blood pressure.

These simple steps help eliminate factors that can falsely raise your blood pressure.

What is the technique to check your blood pressure?

When it comes to accuracy, upper-arm monitors are the preferred choice. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends arm cuff-based devices over wrist monitors because they tend to provide more reliable readings. Research has shown that upper-arm measurements align more closely with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)—the gold standard for assessing blood pressure.

Key Tips for Accurate Blood Pressure Readings:

✔ Use an upper-arm monitor for the most precise measurements.

✔ Keep your arm at heart level while measuring—this applies whether you’re using an upper-arm or wrist monitor.

✔ Choose the right cuff size to ensure accuracy.

Blood Pressure Cuff Sizes:

📏 Small Adult Cuff

📏 Adult Cuff

📏 Large Adult Cuff

📏 Adult Thigh Cuff

Selecting the correct cuff size is crucial—a cuff that’s too small or too large can lead to inaccurate readings. Always check the manufacturer’s sizing guide to find the best fit for your arm.

Choosing the Right Blood Pressure Cuff Size

Selecting the correct cuff size is essential for accurate blood pressure readings. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends choosing a cuff based on your mid-arm circumference:

📏 Small Adult Cuff → 22-26 cm

📏 Adult Cuff → 27-34 cm

📏 Large Adult Cuff → 35-44 cm

📏 Adult Thigh Cuff → 45-52 cm

Why Cuff Size Matters

Using the wrong cuff size can lead to significant inaccuracies:

❌ Too small? May produce falsely high blood pressure readings.

❌ Too large? Can result in falsely low readings.

How to Ensure Accuracy

For precise measurements, choose a cuff with an inflatable bladder that spans approximately 80% of your arm circumference.

🔎 What is a cuff bladder?

It’s the inflatable chamber inside the blood pressure cuff that, when filled with air, compresses the artery to measure blood pressure accurately.

Using the right cuff improves accuracy and ensures reliable blood pressure monitoring at home.

Which Blood Pressure Monitor Should You Buy?

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend the following automated, validated blood pressure monitors for home use:

✅ Omron 10 Series BP7450 (HEM-7342T-Z)

✅ Omron Platinum BP5450 (HEM-7343T-Z)

✅ Omron M6 Comfort

✅ Withings BP-800

(I have no financial ties to these manufacturers.)

These models are known for their accuracy and ease of use, making them great choices for home blood pressure monitoring. However, even the best device won’t provide reliable results unless you follow proper measurement techniques.

Master ICU Vasopressor Management: 8 Shock Resuscitation Tips

Introduction

Vasopressor management can be the difference between life and death in the ICU. If you take care of critically ill patients, these 8 must-know facts will help you make the right call when it matters most. Let’s dive in

Fact #1: Vasopressors Won’t Work in a Dry Tank!

Vasopressors are ineffective in volume-depleted patients. Before reaching for pressors, always ensure adequate volume resuscitation. If hypotension persists despite fluids, then—and only then—consider vasopressors. For most patients, an initial resuscitation with 2-3 liters of crystalloid—preferably a balanced solution like LR or Plasmalyte—is sufficient.

Beware of post-intubation shock in volume-depleted patients: positive pressure ventilation can worsen hypotension by reducing venous return. The remedy is fluids, not vasopressors.

Fact #2: Not All Vasopressors Are Created Equal!

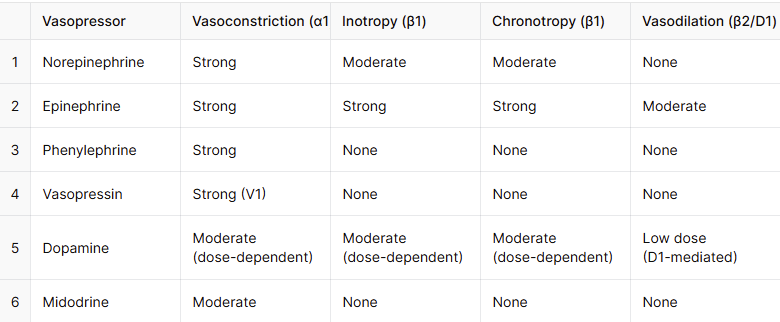

- As all of you know, BP = HR x SV x SVR. This means vasopressors increase BP by working to increase HR (chronotropic effect), increase SV (inotropic effect) or by increasing SVR (vasoconstrictive effect).

- All vasopressors cause vasoconstriction! In addition, Norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine have both chronotropic (Increase the HR) and inotropic effects (Increase SV), while phenylephrine and midodrine are pure vasoconstrictors.

- Vasopressin works differently—it increases SVR via V1 receptors and has no direct inotropic or chronotropic effects.

- Norepinephrine has a more potent vasoconstrictor effect than epinephrine and dopamine, leading to increased systemic vascular resistance (SVR). This vasoconstriction can trigger reflex bradycardia, similar to phenylephrine; however, norepinephrine also has β1 activity, which counteracts this effect, resulting in a stable or only mildly increased heart rate. In contrast, epinephrine and dopamine have stronger β1-mediated chronotropic effects, making them more suitable for bradycardic patients.

Fact #3: Norepinephrine is first line

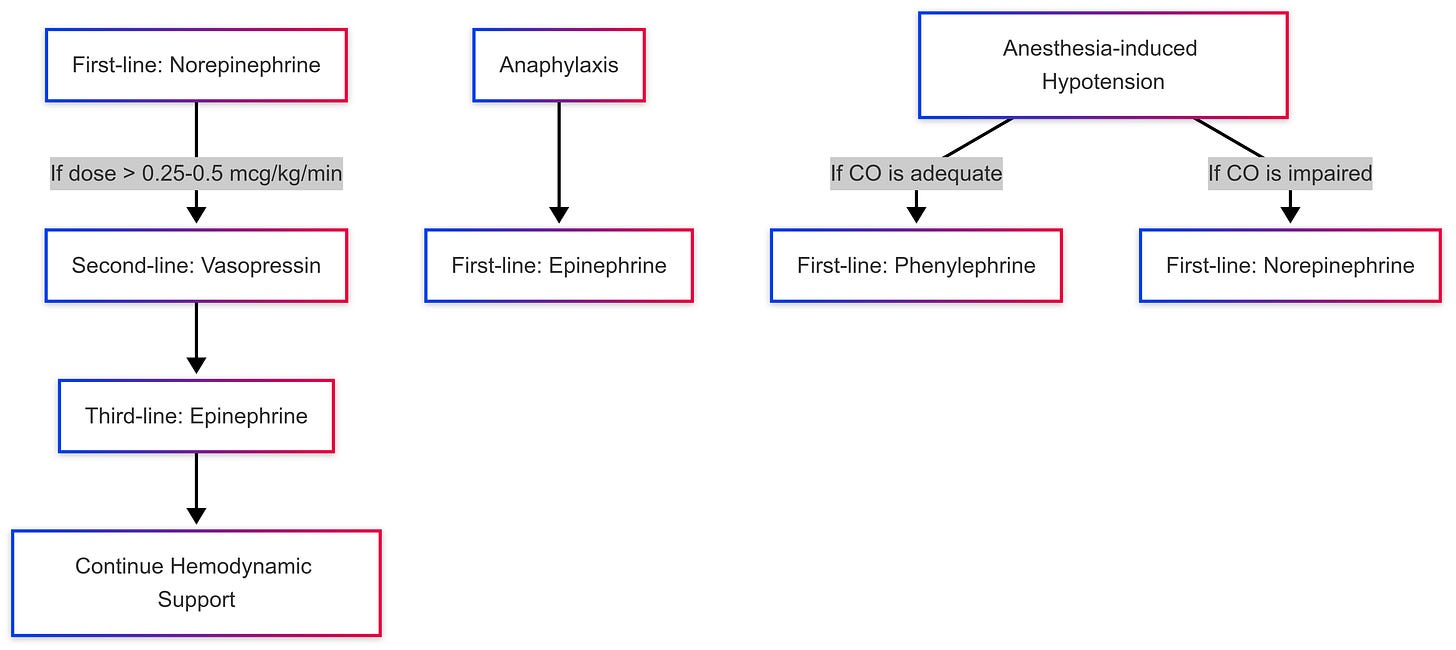

- Norepinephrine is the first-line vasopressor for most types of hypotension, except in anaphylaxis and anesthesia-induced hypotension.

- In anaphylactic shock, Epinephrine is the first-line treatment because it uniquely addresses all life-threatening aspects: α1-mediated vasoconstriction reverses hypotension and airway swelling, β1effect supports cardiac output, and β2 causes bronchodilation and inhibits mast cell degranulation. No other vasopressor provides this combination of effects.

- In anesthesia-induced hypotension, Phenylephrine is preferred unless cardiac output is impaired, in which case norepinephrine is the better choice.

- Vasopressin is an adjunct to norepinephrine to help reduce norepinephrine requirements and mitigate potential side effects. It’s typically added when norepinephrine requirements exceed 0.25 to 0.5 mcg/kg/min (or around 5-15 mcg/min in a 70 kg patient). However, it is primarily studied in septic shock, but it can still be used where Norepinephrine is used.

- Epinephrine is the third vasopressor to add, except in anaphylaxis where it’s considered a first line.

- Besides anesthesia-induced hypotension, phenylephrine is also used when norepinephrine leads to excessive tachycardia.

- Dopamine is no longer a preferred vasopressor due to its higher risk of tachyarrhythmias, increased mortality in septic shock, and unreliable pharmacodynamics with variable receptor effects depending on dose. While it may still be considered in bradycardic shock or when norepinephrine is unavailable, epinephrine remains the preferred choice for bradycardic shock due to its more potent and reliable β1 effects.

- Midodrine is the only commonly used oral vasopressor, which is mainly used in chronic hypotension and weaning of other vasopressors. More soon about weaning.

Fact #4: Mean arterial pressure (MAP) should be targeted when titrating vasopressors in the ICU.

- When titrating vasopressors in critically ill patients, the target mean arterial pressure (MAP) is typically ≥65 mmHg, as it is the best indicator of organ perfusion. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) should not be used as a target, since it fluctuates due to various factors (e.g., pulse pressure variability, arrhythmias, mechanical ventilation) and does not reliably reflect tissue perfusion.

- Some patients may struggle to maintain a MAP of 65 mmHg due to chronically low diastolic blood pressure (DBP), even with high vasopressor doses. Remember that (MAP = SBP + 2(DBP) / 3). In these cases, it is important to determine whether the low DBP is a baseline finding rather than a sign of inadequate perfusion. Reviewing prior vital signs can help assess if the patient normally functions at a lower MAP without adverse effects.

- Suppose a patient has a chronically low DBP but shows no signs of hypoperfusion (e.g., normal mentation, urine output, and lactate levels). In that case, adjusting the MAP target to 60 or even 55 mmHg may be reasonable, rather than unnecessarily escalating vasopressor doses.

Fact #5: Don’t Overlook Steroids in Refractory Shock

- Steroids play a crucial role in the management of refractory shock when patients remain hypotensive despite adequate fluid resuscitation and moderate- to high-dose vasopressors.

- Hydrocortisone is the preferred agent, typically administered at 200 mg per day (given as 50 mg IV every 6 hours).

- Treatment is usually continued for 3–7 days or until vasopressors are discontinued, with tapering considered if therapy exceeds one week.

Moderate- to high-dose vasopressor therapy is defined as norepinephrine or epinephrine doses ≥ 0.25 µg/kg/min for at least 4 hours, with high-dose therapy often exceeding 1 µg/kg/min of norepinephrine equivalent.

Fact #6: Administer Vasopressors via a Central Line Whenever Possible

- Vasopressors should be infused through a central line whenever feasible to minimize the risk of extravasation and tissue injury. However, in emergencies, they may be initiated through a large-bore peripheral IV while central access is being established.

- Central lines include both centrally inserted central catheters (CVCs) (e.g., internal jugular, subclavian, femoral) and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), as they terminate in the central circulation.

- Midlines, however, should generally not be used for vasopressors due to their higher risk of extravasation and inadequate hemodilution in peripheral veins.

Fact #7: Managing Vasopressor Extravasation

If vasopressors infiltrate the surrounding tissue, immediately discontinue the infusion and initiate treatment to minimize tissue damage. The preferred antidote is phentolamine, an α-adrenergic antagonist, which can be injected subcutaneously around the affected area to counteract vasoconstriction and prevent necrosis. Other options include topical nitroglycerin and, in severe cases, hyaluronidase or local saline infiltration to promote drug dispersion.

Fact #8: Weaning Vasopressors: A Stepwise Approach

- Vasopressor weaning should begin once the patient is clinically stable and the MAP is at or above the target without ongoing signs of hypoperfusion. The general principle is to remove the vasopressor contributing the least to maintaining MAP first while keeping the most essential agents until last.

Consider a critically ill patient admitted with severe septic shock, initially started on norepinephrine. As their condition worsened, vasopressin was added, followed by epinephrine, and then phenylephrine for additional support. Now that the patient’s condition has improved, we need to start the weaning process.

Vasopressor Weaning Sequence:

1️⃣ Phenylephrine → First to be discontinued (last added, least contribution).

2️⃣ Epinephrine → Second, unless significant cardiac support is still needed.

3️⃣ Vasopressin → Third, typically when norepinephrine is ≤0.25 mcg/kg/min to avoid rebound hypotension.

4️⃣ Norepinephrine → Last to be weaned, as it is the primary agent maintaining perfusion.

Key Considerations:

- Wean one vasopressor at a time, allowing 4–6 hours between changes to monitor for hypotension.

- If MAP drops, don’t rush to restart the discontinued vasopressor and reconsider the weaning order or adjust the dose of remaining vasopressors.

- Ensure adequate end-organ perfusion (urine output, mental status, lactate clearance) before further titration.

Where is Midodrine’s role in the weaning process?

Midodrine is not a replacement for IV vasopressors but serves as a weaning aid in patients who are stable but still require low-dose pressor support. It can help transition patients out of the ICU faster while maintaining hemodynamic stability.

For example, if you have a patient who is recovering in the ICU but continues to require a low dose of norepinephrine, you can start midodrine 10 mg PO every 8 hours to help getting him off norepinephrine and eventually transfer him out of the ICU.

AKI (Acute kidney injury) in the Hospital: Forget the Textbooks, Focus on This!

Prevention

Four important practical steps to reduce the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) in hospitalized patients:

- Adequate hydration.

- Avoiding hypotension.

- Detecting and treating urine retention early.

- Limiting the use of nephrotoxins.

Let’s break down these points a bit…

Adequate hydration

For most, adequate oral intake provides sufficient hydration. Use IV fluids only when necessary—like in cases of volume depletion or prolonged NPO status.

Precautions:

- Patients with vomiting, diarrhea, fever, or decreased oral intake for any reason have a degree of volume depletion. We must optimize their volume status with IV fluids before introducing nephrotoxic medications, even if their kidney function looks normal.

- Patients on diuretics are at higher risk of dehydration and electrolyte imbalances due to over-diuresis. I always advise my patients to stop taking diuretics if they develop vomiting, diarrhea, fever, or significantly reduced oral intake.

- Patients with rhabdomyolysis and hemolysis are at risk of developing pigment-induced nephropathy particularly when CK > 5000, aggressive IV fluid hydration should be provided to prevent that.

- Patients at risk for contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) such as those with preexisting renal impairment, should receive IVF hydration with isotonic solutions 1 mL/kg/hour starting 6-12 hours before and continuing for 12-24 hours after the procedures.

Avoiding hypotension.

The kidneys are susceptible to low blood pressure, and even brief episodes of hypotension can cause AKI. We must act quickly to stabilize blood pressure and address hemodynamic instability.

Detecting and treating urine retention early.

Routinely palpate the lower abdomen for bladder distension, especially in elderly males with dementia or encephalopathy. If a Foley catheter is in place, confirm it is patent and draining properly.

Limiting the use of nephrotoxins

- Several medications may cause nephrotoxicity! NSAIDs, IV vancomycin, aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, acyclovir, methotrexate, Cyclosporins, tacrolimus, and IVIG are just some of the medications.

- Among NSAIDs, Ketorolac is the most nephrotoxic and should not be used for more than 5 days.

- IV Vancomycin and aminoglycoside levels should be closely monitored, I typically have our pharmacy handle that. We must switch to less nephrotoxic antibiotics as soon as we can.

- IV Acyclovir can cause crystal-induced nephropathy, particularly at higher doses. Ensure patients are well-hydrated before starting therapy and continue IV fluids during treatment unless contraindicated.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are not inherently nephrotoxic. In fact, they are commonly used in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) for their protective effects. However, their use can be associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) in certain situations, particularly in patients with volume depletion, or concurrent use of other nephrotoxic agents.

- Always opt for a less nephrotoxic alternative when an equally effective medication is available.

- Kidney function and urine output should be closely monitored whenever nephrotoxic medications are administered.

In patients with CKD, it’s important to avoid nephrotoxins whenever possible. NSAIDs should be avoided entirely, and contrast agents should only be used if necessary. Additionally, ensure all medications are dosed appropriately for renal impairment.

Diagnosis of AKI

AKI is an abrupt decline in kidney function, reflected by a decline in theGFR. Since direct GFR measurement isn’t practical, AKI is diagnosed based on creatinine accumulation or decreased urine output, using the following criteria:

- Increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours.

- Increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline within 7 days.

- Urine output ≤0.5 mL/kg/hr for 6 hours.

I have three comments on this definition:

- Trend Over Time Matters – AKI is diagnosed based on serial changes, not a single isolated value. Always compare current kidney function to previous results. If prior values are unavailable and the patient presents with abnormal kidney function, assume AKI until proven otherwise.

- BUN is Not Included – Serum creatinine is the preferred marker as it more accurately reflects GFR. BUN levels can be influenced by protein intake, catabolism, GI bleeding, or liver dysfunction, making them less specific for AKI.

- No Creatinine Cutoff – A normal BUN/Cr ratio does not necessarily mean normal kidney function, while an abnormal ratio may indicate chronic kidney disease (CKD) rather than AKI.

The underlying cause

- History and physical exams remain the single most important element in finding out the underlying cause of AKI.

- Patients who are volume-depleted such as those with vomiting, diarrhea, decreased oral intake, and bleeding are likely to have AKI due to renal hypoperfusion or what we call prerenal AKI.

- Patients with signs of volume overload such as peripheral edema and ascites are likely to have a prerenal AKI due to decreased effective circulatory volume. When this happens in patients with congestive heart failure with decreased cardiac output we call it cardiorenal syndrome.

- The development of AKI in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis suggests possible hepatorenal syndrome.

- AKI with urine retention suggests obstructive uropathy or what we call post-renal, this is mainly seen in elderly male patients and those with urinary catheters.

- AKI after hypotension suggests ATN! Remember that even transient episodes of hypotension can cause AKI.

- Medications can cause AKI via different mechanisms:

- ATN such as with vancomycin and aminoglycosides.

- Crystal-induced nephropathy such as methotrexate, acyclovir, amoxicillin, and sulphamethoxazole.

- AIN (Acute interstitial nephritis) such as with beta-lactam antibiotics, NSAIDs, and PPI.

AIN comes to my mind when the H&P doesn’t point out an obvious cause of AKI, I look if there is a history of recent medication use, infections, or autoimmune diseases. Common symptoms include fever, rash, and eosinophilia, although these are not always present.

- The development of AKI in the setting of rhabdomyolysis especially when CK level > 5000 suggests possible pigment-induced nephropathy. Think of rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged immobilized state, heat exertion, trauma, and some drugs. Remember that rhabdomyolysis may cause elevated AST/ALT as well.

- AKI that develops within 48 to 72 hours after contrast exposure suggests contrast-induced nephropathy.

W/U

Even when the cause of AKI seems clear based on the history and physical exam, I always perform a urinalysis and renal ultrasound to look for any evidence of obstruction. I reserve additional urine tests—such as FENa, FEUrea, urine creatinine, cast analysis, and sometimes renal biopsy for cases where the etiology of AKI remains unclear after my initial assessment.

Management of AKI

- When my patient develops AKI, I reflexively do these five things:

- Discontinue any potential nephrotoxin and offending agents.

- Correct and avoid hypotension.

- Ask the pharmacy to renally adjust all medication.

- Switch to a renally safe alternative if possible, for example, switch to LMWH to UFH for DVT prophylaxis or anticoagulation.

- Palpate the patient’s lower abdomen to check for any bladder distension and place a Foley catheter if detected. This is particularly important in elderly gentlemen.

The primary objectives of AKI treatment are to halt further damage, identify and treat the underlying cause, manage any electrolyte disturbances and acidosis, and support the kidneys in recovering full function as efficiently as possible.

Obstructive uropathy

- The treatment of obstructive uropathy involves relieving the obstruction and managing volume and electrolytes.

- Urinary catheterization relieves the obstruction in most cases. I always consult urology with these patients.

- If the obstruction is due to BPH, alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin must be initiated.

- Volume management is crucial in these patients given potential post-obstructive diuresis.

- There is no set rule for a fluid replacement here! Ensuring the patient remains hemodynamic stability is the main goal.

- Some may opt to track UO and replace it with fluids, a 50–75% strategy can be used which means replacing 50-75% of the previous hour’s urine output with IV fluid.

- Post-decompression hematuria may develop with rapid bladder decompression.

Prerenal AKI

- The management of prerenal AKI depends on the cause of decreased renal perfusion.

- Volume depletion:

- Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation with isotonic crystalloid solutions, don’t shy away from using LR or plasmalyte because of the concern of hyperkalemia!

- Bicarb drip should be used instead if metabolic acidosis is present, I use bicarb drip when HCO3 < 22.

- Volume overload:

- IV loop diuretics. Patients with AKI require higher doses of loop diuretics, the starting dose of furosemide is 80 mg once or twice daily, and 2 mg once or twice daily for bumetanide.

Albumin can be administered in hypoalbuminemic patients, It may offer short-term diuretic enhancement and is typically given 15-20 minutes before the IV loop diuretic is given.

- Patients with congestive heart failure and low CO syndrome may require inotropes as well. Please consult cardiology in addition to nephrology if you decide to use inotropes.

- Albumin along with terlipressin or norepinephrine is the treatment of choice for hepato-renal syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis

- Discontinue any potential offending agents as this can lead to partial or complete recovery of renal function.

- If no improvement in kidney function within 5-7 days after stopping the offending drug, corticosteroids are recommended. Prednisone is commonly used, starting at 1 mg/kg/day for 1-2 weeks, followed by a taper over 4-6 weeks. Early initiation of steroids is associated with better outcomes and reduced risk of chronic kidney disease.

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN)

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is probably the most common form of AKI in critically ill patients.

- It frequently results in oliguria, anuria, and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Remember that oliguria is defined as < 0.5 mL/kg/hr over 6 hours and anurea is defined when UO is less than 100 mL/day.

- Anuric or oligouric AKI always makes me nervous, I consult nephrology right away in these patients as life-threatening hyperkalemia and acidosis can develop quickly requiring RRT.

- Don’t be deceived by the initial normal K! As long as they are oliguric or anuric, potassium likely will rise despite hyperkalemia management, the same applies to metabolic acidosis.

Crystal-induced and pigment-induced nephropathy

The treatment of crystal-induced and pigment-induced nephropathy is similar and involves discontinuing the offending agent and providing supportive care with IV fluid resuscitation. In some cases, urine alkalinization may be necessary. Nephrology consultation is essential to optimize management and minimize the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Initiating Renal replacement therapy (RRT)

- The Nephrology team typically decides when to initiate RRT, whether early or late, and whether to use CRRT or intermittent HD.

- CRRT is typically chosen in patients with hemodynamic instability who can’t handle the fluid shift used in regular HD.

- Critical hyperkalemia and severe metabolic acidosis are the two main reasons for emergent RRT in critically ill patients.

Remember that for prompt removal of potassium and acids, traditional HD is the way to go! CRRT is pretty slow in fixing that!

- Volume overload is another indication of RRT in ATN patients! Before starting RRT, if the patient is stable, a high-dose loop diuretic challenge can help assess responsiveness. Typically, we give IV furosemide at 1 mg/kg (or equivalent). If urine output remains ≤600 mL after 6 hours, it suggests poor response and a likely need for dialysis.

- RRT is also indicated for uremic complications such as encephalopathy, pericarditis, and bleeding. RRT is also used for some toxins removal.

- I understand that some of you may consult nephrology for every case of AKI, but that’s not always necessary. Many cases, such as AKI due to volume depletion, are straightforward and typically resolve with IV fluid resuscitation. Let’s reserve nephrology consults for more complex or severe cases, allowing them to focus on the situations that truly require their expertise!

Monitoring

- Patients with AKI should have their Urine output (UO), electrolytes, and kidney function closely monitored.

- While urine output is routinely monitored in critically ill patients, it may not be tracked as closely for those on the regular hospital floor. We must relay the importance of tracking urine output to patients and nurses.

I know we aim to minimize Foley catheter use, but if it’s the only way to accurately measure urine output, we should use it. Urine output offers valuable prognostic information and guides further treatment decisions as we explained earlier.

- AKI is a dynamic process with a continuously changing GFR and creatinine clearance and for that reason, serial labs for kidney functions and electrolytes including HCO3 – labeled as CO2 on BMP/CMP- must be obtained!

- For critically ill patients, particularly those with oliguria or anuria, key labs such as electrolytes, creatinine, and acid-base status should be monitored every 6–8 hours (or up to 12 hours, depending on clinical context). These patients are at high risk for rapid deterioration, including life-threatening hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis. A single normal potassium (K) level or mildly elevated creatinine on a basic metabolic panel (BMP) should not provide false reassurance, as values can shift abruptly in unstable clinical conditions.

- For stable inpatients with adequate urine output, daily laboratory monitoring is typically sufficient. However, more frequent testing (e.g., every 12–24 hours) is warranted if significant electrolyte imbalances, worsening renal function, or other clinical concerns arise.

Prognosis

- AKI due to volume depletion and obstructive uropathy resolves quickly if prompt intervention is provided.

- AKI from ATN may take weeks to months to recover, depending on the severity of tubular injury and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease). Some patients may develop residual CKD or progress to ESRD.

- In AIN, Kidney function typically improves within weeks if the offending drug is stopped and steroids are initiated early.

- In crystal-induced nephropathy, recovery within days with early intervention including rapid hydration, urinary alkalinization, and discontinuing the offending drugs.

- In pigment-induced AKI, aggressive IV fluids to flush out nephrotoxic pigments (myoglobin, hemoglobin) can prevent permanent damage. However, severe cases may still progress to ATN or CKD.

Contrast or noncontrast CT, whic one to order.

Ordering a CT (or CAT) scan and wondering whether contrast is needed? And if you do need contrast, should it be IV or oral? Let’s make this simple for you.

In this post, we’ll break down when to order non-contrast CT, contrast CT, and the different types of contrast to consider (oral, IV, or both). You’ll have a clear framework to guide your decisions by the end.

Types of Contrast

Contrast can be administered in three ways:

- Oral contrast: Helps visualize the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Rectal contrast: Occasionally used for imaging the lower GI tract.

- IV contrast: Highlights blood vessels, organs, and certain tissues.

1. When to Use Oral or Rectal Contrast

The only times you’ll need oral or rectal contrast are:

- GI perforation or anastomosis leak: Use water-soluble iodinated contrast (e.g., Gastrografin) instead of barium-based contrast.

- Distal colonic or rectal perforation/leak: Consider rectal contrast.

Important Note: Oral contrast is unnecessary for diagnosing small bowel obstruction (SBO). Use IV contrast with CT abdomen/pelvis for SBO.

2. When to Use IV Contrast

Use IV contrast for:

- Cancer: Evaluating suspicious lesions or staging.

- Exceptions: Low-dose lung cancer screening, colon cancer screening (CT colonography), pulmonary nodule follow-up, and lymphoma assessment.

- Infections: Abscesses, empyema, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or infected hardware.

- Trauma with penetrating or vascular injuries. if there are no penetrating or vascular injuries then there is no need to give IV contrast

- Inflammatory conditions: Such as IBD, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and appendicitis.

- Exception: Interstitial lung disease (ILD) assessment with high-resolution CT (HRCT)—no IV contrast needed.

- Infarction/Ischemia: This includes kidney infarcts and ischemic bowel.

- Exception: For brain or lung infarctions, non-contrast CT is preferred.

- Vascular conditions: Thrombosis, dissection, aneurysms, or pseudoaneurysms. Use CT angiography (requires IV contrast).

3. When to Order Non-Contrast CT

Non-contrast CT is sufficient for:

- Initial stroke evaluation.

- Hematomas: Retroperitoneal hematomas (although IV contrast can also be used).

- Kidney stones.

- Musculoskeletal issues: Fractures and spinal diseases (if infection isn’t suspected).

- Non-penetrating trauma.

- Interstitial lung disease (HRCT).

- Screenings:

- Low-dose lung cancer screening (LDCT).

- Coronary calcium scoring.

- CT colonography.

4. Real-Life Clinical Scenarios

Here are practical examples to solidify your understanding:

Scenario 1: Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

A 40-year-old woman on birth control pills presents with sudden shortness of breath. PE is suspected. PE is a vascular condition.

Order: CT chest angiography with IV contrast.

Scenario 2: Diverticulitis

A 65-year-old patient with LLQ abdominal pain. Acute diverticulitis is suspected.

Acute diverticulitis is an inflammatory process.

Order: CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast.

Scenario 3: Trauma and Anticoagulation

An 80-year-old man on warfarin falls and sustains a head laceration. CT of head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis ordered. On exam, he only had some head lacerations and no signs of other injuries.

The patient had a trauma without penetrating or vascular injuries, hematoma also needs to be ruled out as he was on anticoagulation.

Order: Non-contrast CT.

Scenario 4: Kidney Stones

A 30-year-old woman with recurrent flank pain and a history of kidney stones, and renal colic was suspected to be the culprit.

Order: Non-contrast CT abdomen/pelvis.

Scenario 5: Severe Abdominal Pain

A 45-year-old patient with severe abdominal pain and vomiting, on physical exam, his abdomen remained soft but with diffuse tenderness, The ED physician ordered CT abd/pelvis.

Order: CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast (oral contrast is unnecessary, particularly with vomiting).

Scenario 6: Suspected Stroke

80-year-old man with sudden aphasia. Stroke suspected.

Order: Non-contrast CT head.

Scenario 7: Infection with Hardware

58-year-old woman s/p back surgery involving hardware placement presented with back pain and surgical wound discharge. MRI is unavailable.

Order: CT lumbar spine with IV contrast (infection suspected).

Final Tips

- Always assess for contrast allergies and ensure normal kidney function before ordering contrast studies.

- When in doubt, consider the clinical scenario—contrast should add diagnostic value and improve outcomes.