1. Norepinephrine- your bread and butter.

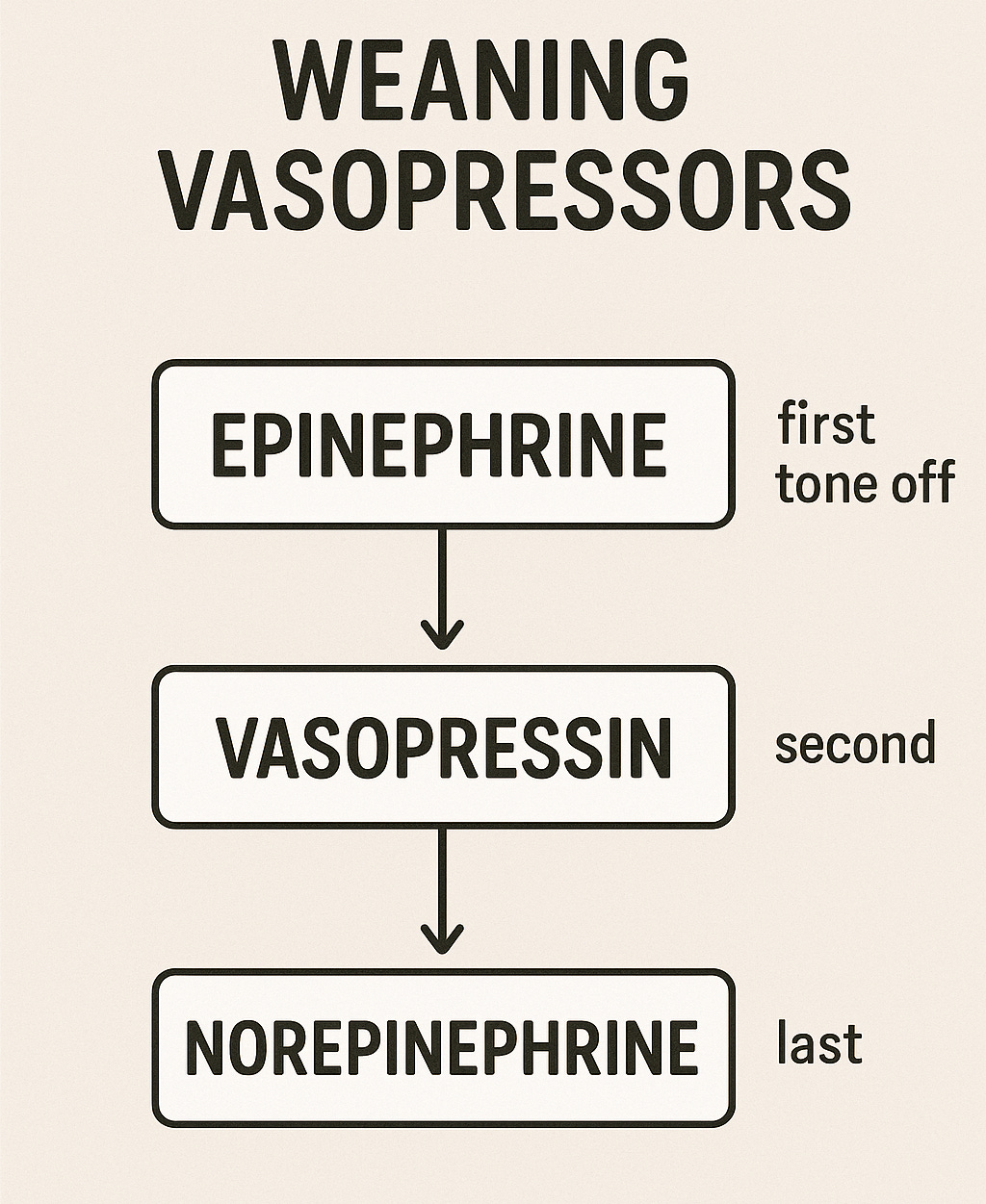

- It’s the first-line vasopressor for almost all types of shock — except anaphylaxis, where epinephrine comes first.

- When your patient becomes hypotensive, always think fluids first. Vasopressors don’t work in a dry tank. Unless the patient is in pulmonary edema, give 2–3 liters of isotonic fluids. If hypotension persists, then start norepinephrine.

- Dosing: Start at 0.02–0.05 mcg/kg/min and titrate to keep MAP above 65.

- Access: A central line is preferred but not necessary! Don’t delay therapy — norepinephrine can be started safely through a good peripheral IV right away.

Guidelines from IDSA and SCCM emphasize: in shock, start peripherally if needed. Central access can be placed once higher doses, multiple agents, or prolonged infusions are expected.

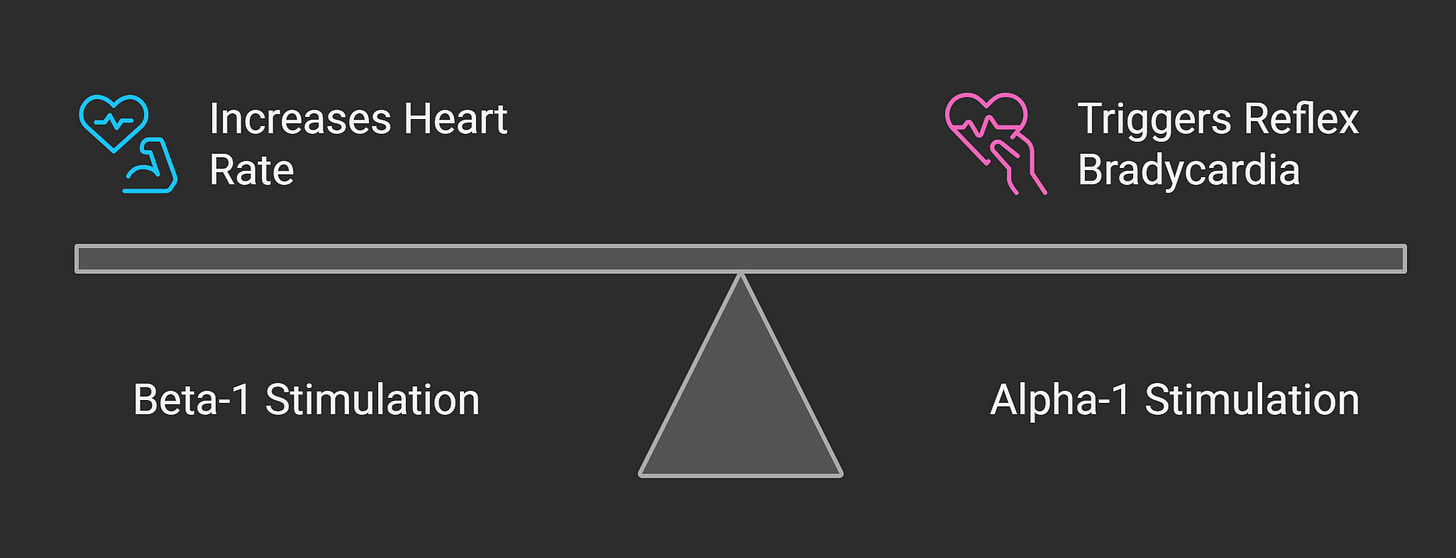

- Norepinephrine has a balanced effect on heart rate; beta-1 stimulation increases HR, but vasoconstriction from alpha-1 stimulation triggers reflex bradycardia — so the two often offset, and heart rate remains stable.

2. Vasopressin — the quiet sidekick.

- It’s your norepinephrine’s best friend.

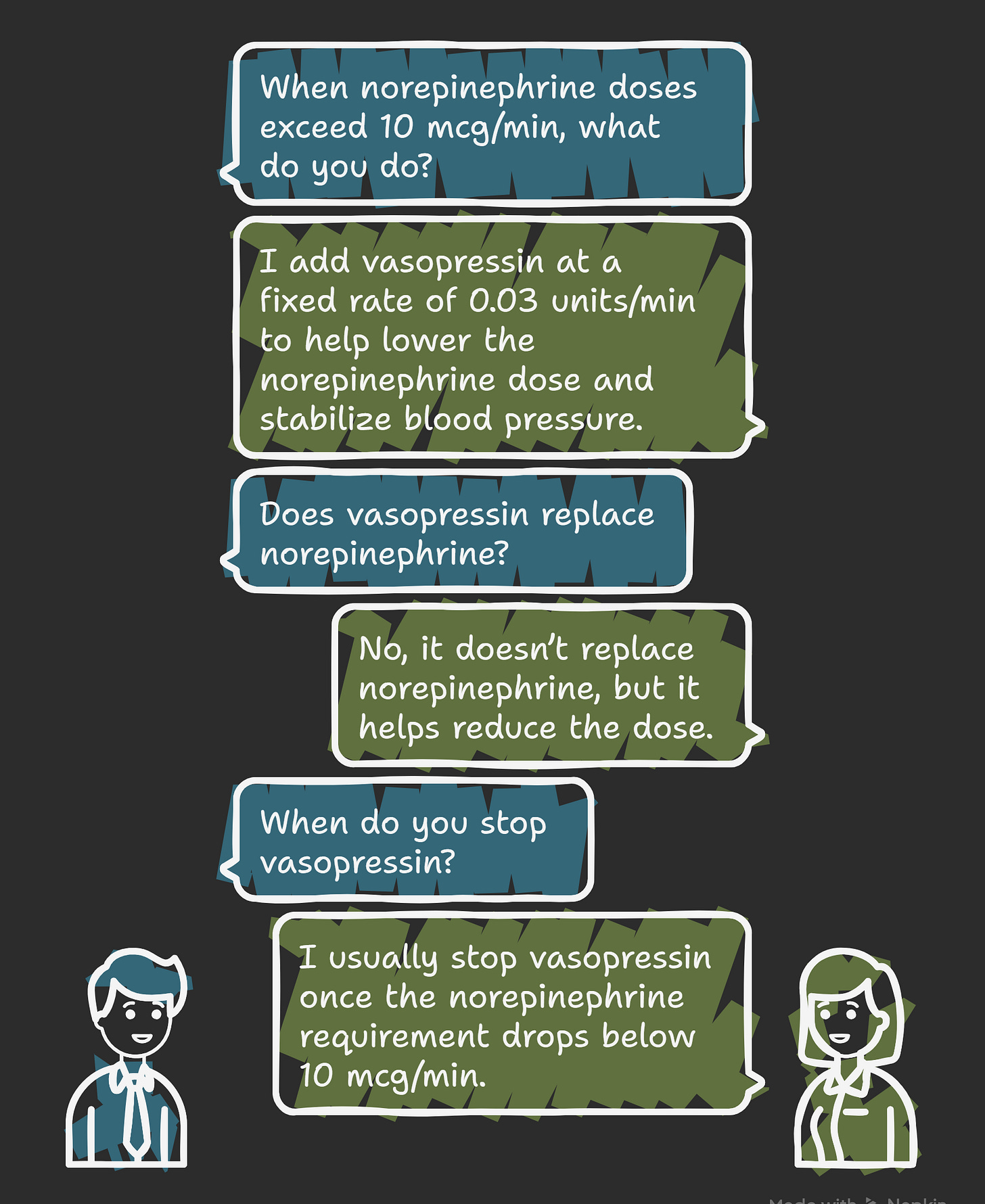

- When norepinephrine doses creep above 10 mcg/min, I add vasopressin at a fixed rate of 0.03 units/min. It doesn’t replace norepinephrine — but it helps bring the dose down and stabilize blood pressure.

- Because it’s a pure vasoconstrictor, there’s no risk of tachycardia like with catecholamines.

- And when things improve, I usually take vasopressin away once the norepinephrine requirement drops back below 10 mcg/min.

3. Epinephrine — the adrenaline shot: shock, stridor, and the stormy heart!

- It’s my go-to vasopressor after norepinephrine and vasopressin, except in:

- Anaphylaxis, epinephrine comes first.

- Hypotensive and bradycardic patients (Dopamine can be used here as well).

- Its potent β2 activity also makes it a powerful bronchodilator — something to remember in life-threatening asthma exacerbations.

- Inhaled racemic epinephrine is used for stridor management.

- And don’t be surprised if lactate rises after starting an epinephrine drip — that’s an expected, short-term effect of adrenergic stimulation, not automatically a sign of shock worsening. Always interpret lactate in context.

- Dosing: For shock, start at 0.01–0.05 mcg/kg/min. Remember, this is very different from the much higher IV bolus doses used during a code.

Compared with norepinephrine, it has stronger β1 activity and weaker α1 activity, which means it’s more likely to cause tachyarrhythmias.

4. Fentanyl — the smooth operator

- Smooth pain control, fast on, fast off. It’s usually the first-line agent for sedation and analgesia in ventilated patients. Adding a sedative to fentanyl isn’t automatic, but only if extra sedation is needed.

- It causes minimal hypotension since it doesn’t trigger histamine release like morphine or other opioids.

- Central line not required.

- Safe in both renal and hepatic impairment.

5. Dexmedetomidine –The gentle sedative:

- It keeps patients calm without shutting down their drive to breathe. Compared to most sedatives, respiratory depression is minimal.

- It doesn’t just calm; it also provides a touch of analgesia, offering comfort alongside sedation.

- Precedex is also a powerful tool in delirium management — especially hyperactive delirium. Think of it when you’re faced with a combative, delirious patient, once you’ve ruled out reversible causes.

- Typical ICU infusion: 0.2–0.7 mcg/kg/hr. You can go up to 1.5 mcg/kg/hr in select cases, but higher doses mean higher side effects. I usually avoid the loading dose — it can trigger significant hypotension or bradycardia in unstable patients.

- Side effects to watch for: hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, and tachycardia. Bradycardia, in particular, happens in about 5% of adults — if it doesn’t resolve, reduce or stop the infusion.

- Rebound tachycardia and hypertension can occur after abrupt discontinuation, so taper when possible.

- No central line needed. A good peripheral IV works just fine.

6. Propofol — fast on, fast off.

- Excellent for deep sedation, and I often add it when fentanyl and dexmedetomidine aren’t enough.

- Be prepared for hypotension. It’s common, especially in volume-depleted patients. Ensure your patient is adequately fluid-resuscitated when starting propofol. If hypotension develops, stop or reduce propofol, give 1–2 liters of isotonic fluid, and reassess. Some patients may need a low-dose vasopressor to counteract it.

- Monitoring matters:

- Check triglycerides at baseline and at least twice weekly on continuous infusions. Stop propofol if triglycerides exceed 400–500 mg/dL.

- Watch for Propofol Infusion Syndrome (PRIS) — rare but often fatal. It’s seen with prolonged, high-dose infusions (>4–5 mg/kg/hr for >48 hours). Look for severe metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, lipemia, rhabdomyolysis, hepatomegaly, renal failure, and EKG changes (like a Brugada-like pattern). If you suspect PRIS — stop propofol immediately.

- Access: Central line not required — propofol can be safely run through a good peripheral IV.

7. Amiodarone – The rhythm tamer

- I use it most often in atrial fibrillation with RVR when patients can’t tolerate beta blockers or calcium channel blockers because of hypotension.

- It’s my go-to medication for wide complex tachycardia when the underlying rhythm isn’t clear — but avoid it in irregular WCT because of the risk of an accessory pathway. The same caution applies to beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers.

- Dosing: Start with 150 mg IV bolus over 10–30 minutes, then 1 mg/hr for 6 hours, then 0.5 mg/hr for 18 hours.

- Amiodarone is less likely to cause hypotension than beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers. When it does, it’s usually from giving the bolus too quickly — so administer it slowly.

- Central line not required — peripheral use is safe.

- Avoid if QTc > 500 ms.

- Keep an eye on LFTs — hepatotoxicity is a known risk.

- Transitioning to oral therapy isn’t automatic; it depends on whether the patient really needs ongoing antiarrhythmic therapy.

8. Insulin (IV infusion) – The silent stabilizer.

- Insulin drips are the go-to in the ICU for rapid glucose control. Don’t shy away from using them — it isn’t just for DKA or HHS.

- Continuous insulin infusion (Insulin drip) is also used in severe hypertriglyceridemia to reduce the risk of pancreatitis if plasmapheresis isn’t available. Here, insulin is given at a fixed weight-based dose, not titrated to glucose levels.

- Most ICUs have their standard insulin protocols — so make sure you’re familiar with your unit’s.

- ⚠️ Always check potassium before starting. I avoid insulin infusions if K is <3.3–3.5 mEq/L until it’s corrected.

- Access: Central line not required — insulin drips are safe through a peripheral IV.

- And if you want the bigger picture, I’ve got a full video on all insulin types and uses — you can watch here and here

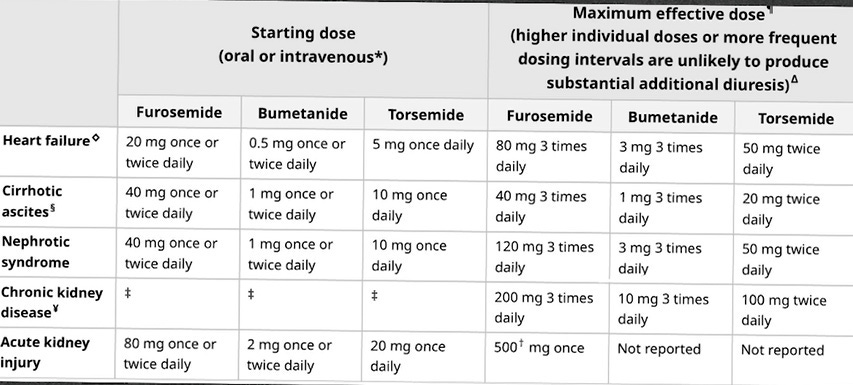

9. Loop diuretics-The ICU candies:

- Furosemide, torsemide, and bumetanide — all sulfa-based. The oddball is ethacrynic acid, which is the only non-sulfa loop diuretic, reserved for patients with true sulfa allergy.

- No cross-reactivity with sulfa antibiotics — so you’re safe to use loops in those patients.

- They also cause calcium excretion and produce dilute urine, unlike thiazides, which concentrate it.

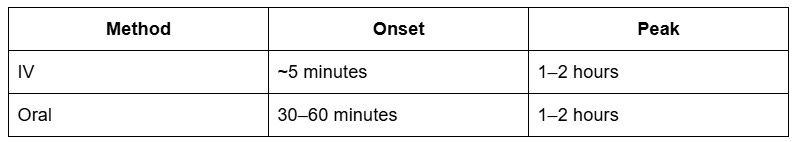

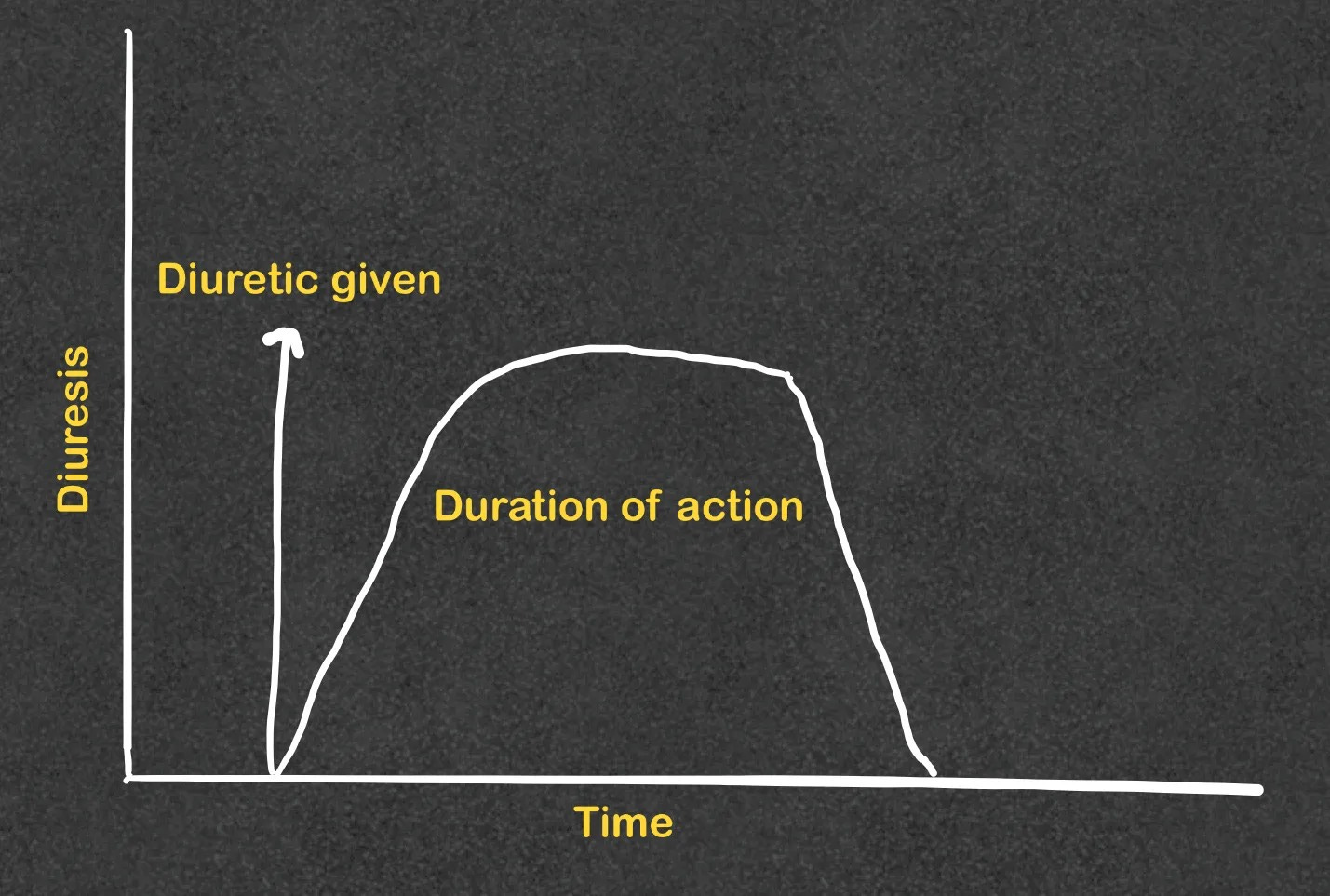

Onset and peak of loop diuretics:

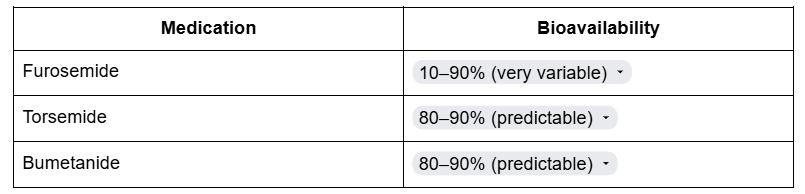

Bioavailability:

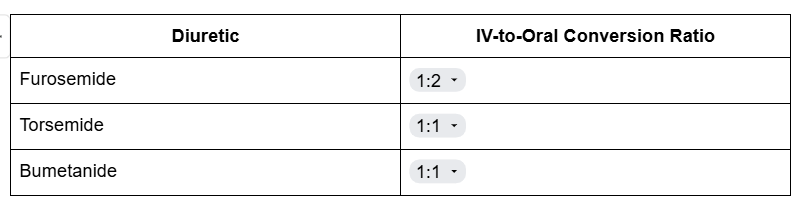

IV-to-oral conversion:

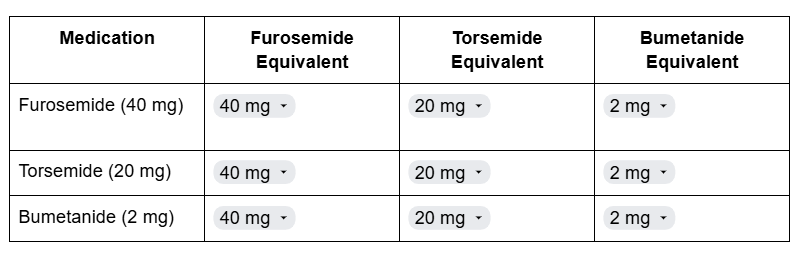

Loop-to-loop conversion:

Two key pearls people often miss:

- Tolerance: Loops last ~6–8 hours, then effect drops off. That’s why we give repeat doses or run a continuous infusion for aggressive diuresis.

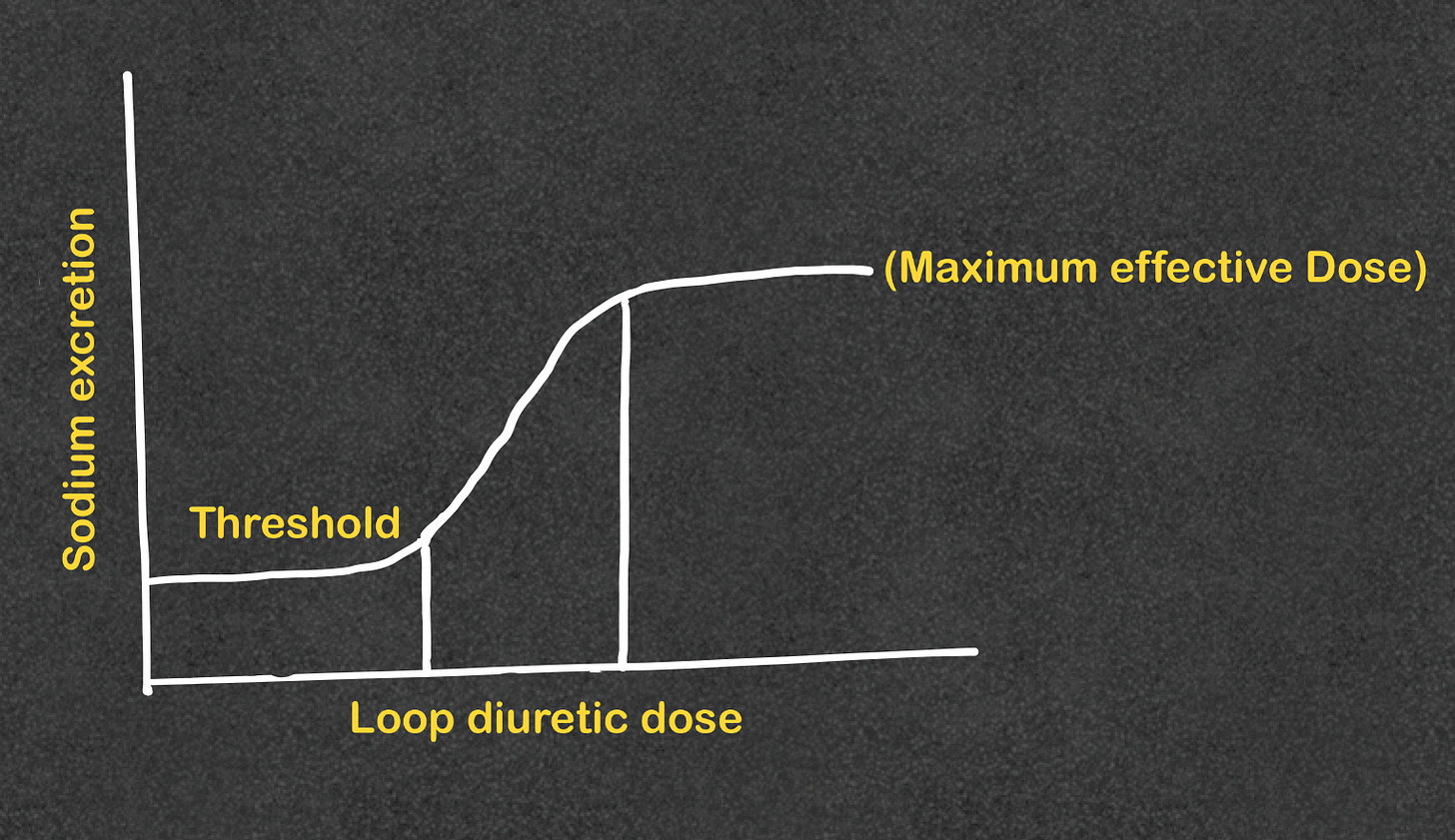

Loop diuretic’s action drops to zero after 6-8 hours - Threshold dose: Below a certain dose, you get zero effect. Threshold varies by condition.

- The maximum effective dose: The dose at which you get the maximum diuretic effect.

Loop diuretics threshold and maximum effective dose!

Safety reminders

- Ototoxicity is possible, especially with high IV doses.

- Electrolyte monitoring is essential — replete potassium early and often.

- Consider spironolactone as a partner in resistant fluid overload.

10. Hydrocortisone – The shock helper.

- For refractory septic shock, defined as patients who remain hypotensive despite fluids and vasopressors (often ≥2 agents or high-dose norepinephrine.

- 50 mg IV q6h or continuous infusion; If used for more than 3–5 days in septic shock, we usually taper — not because of adrenal suppression (that risk needs ~3 weeks), but to prevent rebound hypotension when coming off pressors.

- Central line: Not required — safe peripherally.

- Pro tip: “Steroids in septic shock are like jumper cables — they won’t fix the engine, but they might get you running.”

10 Medications You Must Master Before Your ICU Rotation

Positive troponins! MI or not?

Comprehensive Guide to Antibiotic Spectrum: Gram-Positive, Gram-Negative, and Anaerobic Coverage