Introduction

Vasopressor management can be the difference between life and death in the ICU. If you take care of critically ill patients, these 8 must-know facts will help you make the right call when it matters most. Let’s dive in

Fact #1: Vasopressors Won’t Work in a Dry Tank!

Vasopressors are ineffective in volume-depleted patients. Before reaching for pressors, always ensure adequate volume resuscitation. If hypotension persists despite fluids, then—and only then—consider vasopressors. For most patients, an initial resuscitation with 2-3 liters of crystalloid—preferably a balanced solution like LR or Plasmalyte—is sufficient.

Beware of post-intubation shock in volume-depleted patients: positive pressure ventilation can worsen hypotension by reducing venous return. The remedy is fluids, not vasopressors.

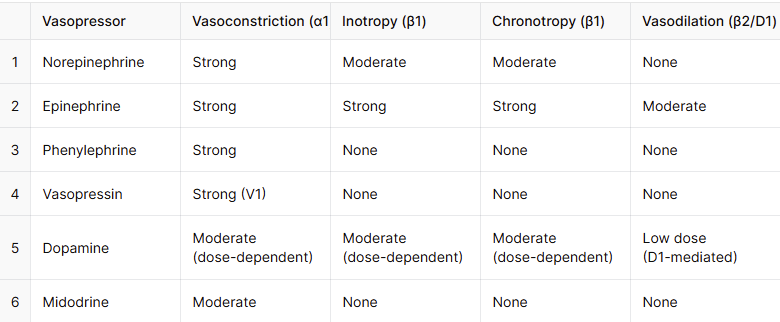

Fact #2: Not All Vasopressors Are Created Equal!

- As all of you know, BP = HR x SV x SVR. This means vasopressors increase BP by working to increase HR (chronotropic effect), increase SV (inotropic effect) or by increasing SVR (vasoconstrictive effect).

- All vasopressors cause vasoconstriction! In addition, Norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine have both chronotropic (Increase the HR) and inotropic effects (Increase SV), while phenylephrine and midodrine are pure vasoconstrictors.

- Vasopressin works differently—it increases SVR via V1 receptors and has no direct inotropic or chronotropic effects.

- Norepinephrine has a more potent vasoconstrictor effect than epinephrine and dopamine, leading to increased systemic vascular resistance (SVR). This vasoconstriction can trigger reflex bradycardia, similar to phenylephrine; however, norepinephrine also has β1 activity, which counteracts this effect, resulting in a stable or only mildly increased heart rate. In contrast, epinephrine and dopamine have stronger β1-mediated chronotropic effects, making them more suitable for bradycardic patients.

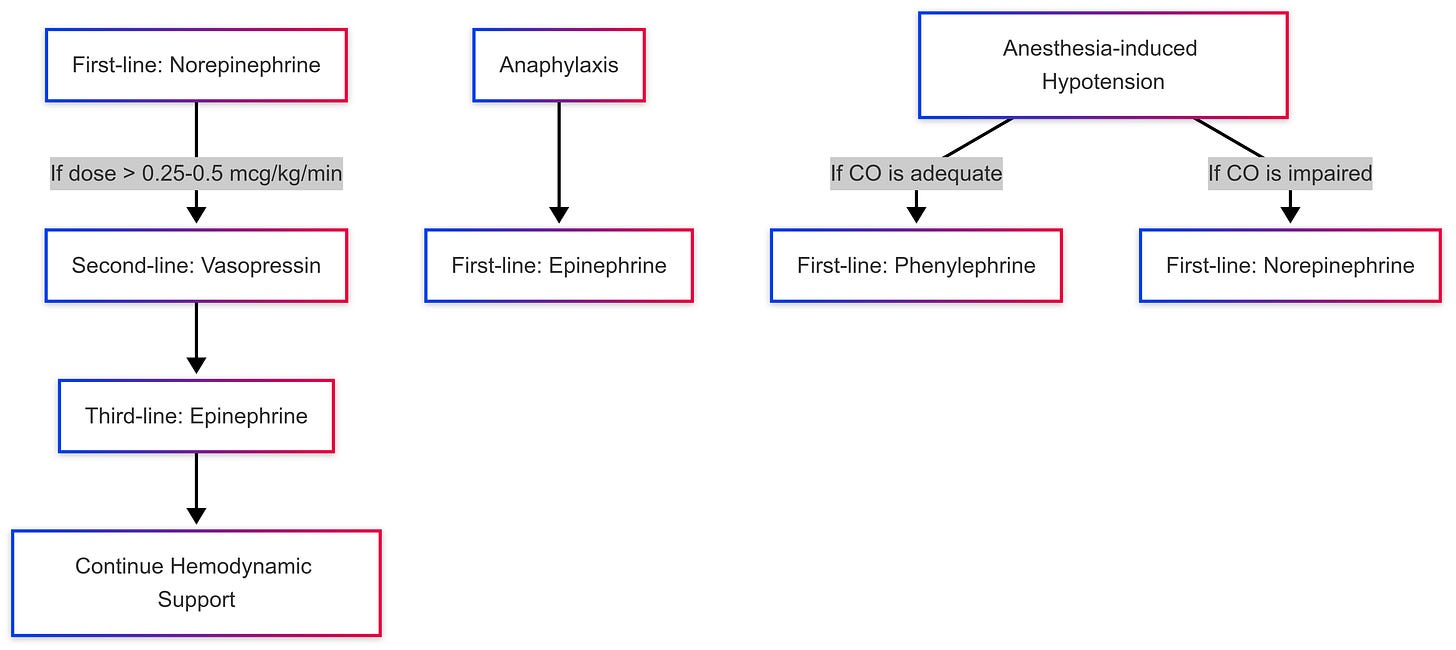

Fact #3: Norepinephrine is first line

- Norepinephrine is the first-line vasopressor for most types of hypotension, except in anaphylaxis and anesthesia-induced hypotension.

- In anaphylactic shock, Epinephrine is the first-line treatment because it uniquely addresses all life-threatening aspects: α1-mediated vasoconstriction reverses hypotension and airway swelling, β1effect supports cardiac output, and β2 causes bronchodilation and inhibits mast cell degranulation. No other vasopressor provides this combination of effects.

- In anesthesia-induced hypotension, Phenylephrine is preferred unless cardiac output is impaired, in which case norepinephrine is the better choice.

- Vasopressin is an adjunct to norepinephrine to help reduce norepinephrine requirements and mitigate potential side effects. It’s typically added when norepinephrine requirements exceed 0.25 to 0.5 mcg/kg/min (or around 5-15 mcg/min in a 70 kg patient). However, it is primarily studied in septic shock, but it can still be used where Norepinephrine is used.

- Epinephrine is the third vasopressor to add, except in anaphylaxis where it’s considered a first line.

- Besides anesthesia-induced hypotension, phenylephrine is also used when norepinephrine leads to excessive tachycardia.

- Dopamine is no longer a preferred vasopressor due to its higher risk of tachyarrhythmias, increased mortality in septic shock, and unreliable pharmacodynamics with variable receptor effects depending on dose. While it may still be considered in bradycardic shock or when norepinephrine is unavailable, epinephrine remains the preferred choice for bradycardic shock due to its more potent and reliable β1 effects.

- Midodrine is the only commonly used oral vasopressor, which is mainly used in chronic hypotension and weaning of other vasopressors. More soon about weaning.

Fact #4: Mean arterial pressure (MAP) should be targeted when titrating vasopressors in the ICU.

- When titrating vasopressors in critically ill patients, the target mean arterial pressure (MAP) is typically ≥65 mmHg, as it is the best indicator of organ perfusion. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) should not be used as a target, since it fluctuates due to various factors (e.g., pulse pressure variability, arrhythmias, mechanical ventilation) and does not reliably reflect tissue perfusion.

- Some patients may struggle to maintain a MAP of 65 mmHg due to chronically low diastolic blood pressure (DBP), even with high vasopressor doses. Remember that (MAP = SBP + 2(DBP) / 3). In these cases, it is important to determine whether the low DBP is a baseline finding rather than a sign of inadequate perfusion. Reviewing prior vital signs can help assess if the patient normally functions at a lower MAP without adverse effects.

- Suppose a patient has a chronically low DBP but shows no signs of hypoperfusion (e.g., normal mentation, urine output, and lactate levels). In that case, adjusting the MAP target to 60 or even 55 mmHg may be reasonable, rather than unnecessarily escalating vasopressor doses.

Fact #5: Don’t Overlook Steroids in Refractory Shock

- Steroids play a crucial role in the management of refractory shock when patients remain hypotensive despite adequate fluid resuscitation and moderate- to high-dose vasopressors.

- Hydrocortisone is the preferred agent, typically administered at 200 mg per day (given as 50 mg IV every 6 hours).

- Treatment is usually continued for 3–7 days or until vasopressors are discontinued, with tapering considered if therapy exceeds one week.

Moderate- to high-dose vasopressor therapy is defined as norepinephrine or epinephrine doses ≥ 0.25 µg/kg/min for at least 4 hours, with high-dose therapy often exceeding 1 µg/kg/min of norepinephrine equivalent.

Fact #6: Administer Vasopressors via a Central Line Whenever Possible

- Vasopressors should be infused through a central line whenever feasible to minimize the risk of extravasation and tissue injury. However, in emergencies, they may be initiated through a large-bore peripheral IV while central access is being established.

- Central lines include both centrally inserted central catheters (CVCs) (e.g., internal jugular, subclavian, femoral) and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), as they terminate in the central circulation.

- Midlines, however, should generally not be used for vasopressors due to their higher risk of extravasation and inadequate hemodilution in peripheral veins.

Fact #7: Managing Vasopressor Extravasation

If vasopressors infiltrate the surrounding tissue, immediately discontinue the infusion and initiate treatment to minimize tissue damage. The preferred antidote is phentolamine, an α-adrenergic antagonist, which can be injected subcutaneously around the affected area to counteract vasoconstriction and prevent necrosis. Other options include topical nitroglycerin and, in severe cases, hyaluronidase or local saline infiltration to promote drug dispersion.

Fact #8: Weaning Vasopressors: A Stepwise Approach

- Vasopressor weaning should begin once the patient is clinically stable and the MAP is at or above the target without ongoing signs of hypoperfusion. The general principle is to remove the vasopressor contributing the least to maintaining MAP first while keeping the most essential agents until last.

Consider a critically ill patient admitted with severe septic shock, initially started on norepinephrine. As their condition worsened, vasopressin was added, followed by epinephrine, and then phenylephrine for additional support. Now that the patient’s condition has improved, we need to start the weaning process.

Vasopressor Weaning Sequence:

1️⃣ Phenylephrine → First to be discontinued (last added, least contribution).

2️⃣ Epinephrine → Second, unless significant cardiac support is still needed.

3️⃣ Vasopressin → Third, typically when norepinephrine is ≤0.25 mcg/kg/min to avoid rebound hypotension.

4️⃣ Norepinephrine → Last to be weaned, as it is the primary agent maintaining perfusion.

Key Considerations:

- Wean one vasopressor at a time, allowing 4–6 hours between changes to monitor for hypotension.

- If MAP drops, don’t rush to restart the discontinued vasopressor and reconsider the weaning order or adjust the dose of remaining vasopressors.

- Ensure adequate end-organ perfusion (urine output, mental status, lactate clearance) before further titration.

Where is Midodrine’s role in the weaning process?

Midodrine is not a replacement for IV vasopressors but serves as a weaning aid in patients who are stable but still require low-dose pressor support. It can help transition patients out of the ICU faster while maintaining hemodynamic stability.

For example, if you have a patient who is recovering in the ICU but continues to require a low dose of norepinephrine, you can start midodrine 10 mg PO every 8 hours to help getting him off norepinephrine and eventually transfer him out of the ICU.

10 Medications You Must Master Before Your ICU Rotation

Positive troponins! MI or not?

Comprehensive Guide to Antibiotic Spectrum: Gram-Positive, Gram-Negative, and Anaerobic Coverage