Key Takeaways at a Glance

(For those who just need the pearls — read this first!)

- NGT = short term, PEG = long term — NGTs are for ≤ 4–6 weeks; PEGs for prolonged enteral feeding.

- Use NGT for dysphagia, mechanical ventilation, nutritional failure, or gastric decompression.

- Absolute contraindications: facial trauma for NGT; ascites / peritonitis for PEG.

- Relative cautions: recent GI bleed or cirrhosis with varices → use soft, small-bore tubes.

- Always confirm placement by X-ray before first use — bedside checks alone aren’t enough.

- Prevent aspiration: keep HOB 30–45°, use continuous pump feeds when possible.

- Skip routine residual checks — focus on clinical intolerance (nausea, distension, vomiting).

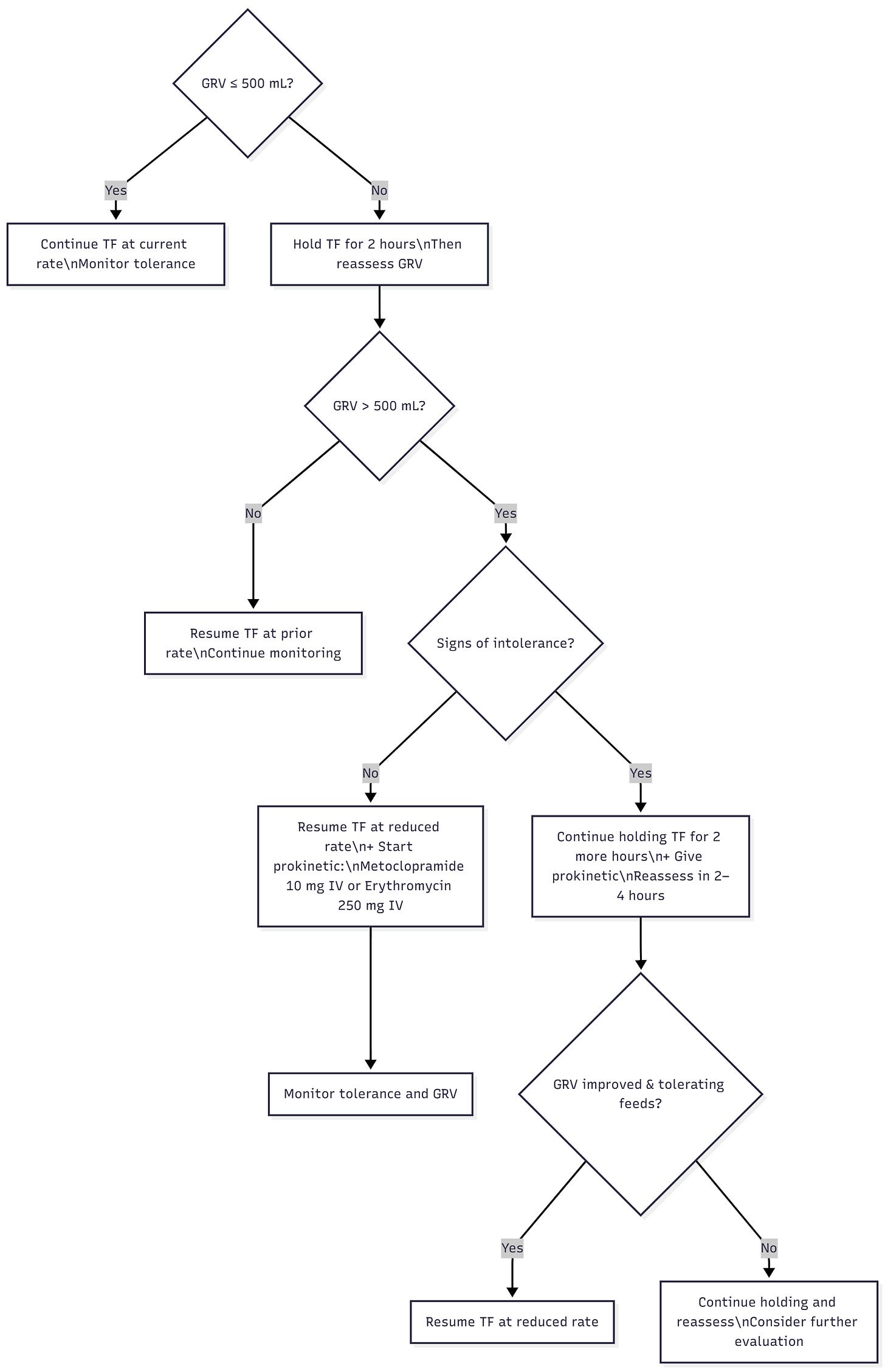

- If GRV > 500 mL: hold 2 hrs → reassess → if persists w/o intolerance, restart slower + prokinetic; if intolerance, continue hold + recheck in 2–4 hrs.

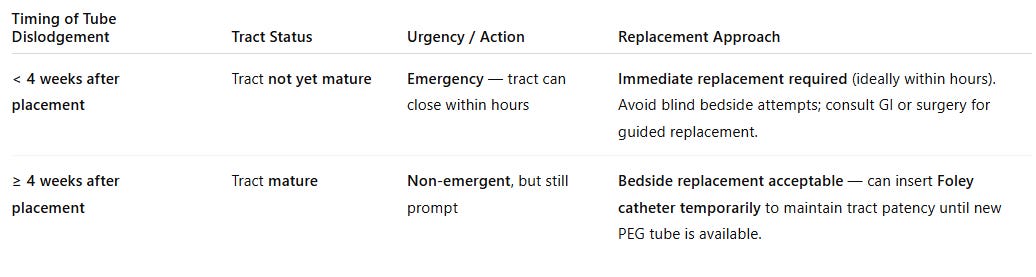

- PEG dislodgement < 4 wks = emergency; ≥ 4 wks: replace bedside with Foley temporarily.

- Prevent clogs: flush before / after meds + feeds, avoid mixing drugs, use warm water ± enzymes if blocked.

Introduction

An NGT, or nasogastric tube, is a flexible tube inserted through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach, and sometimes down to the jejunum, also known as NJ tubes.

A gastrostomy tube is inserted directly through the abdominal wall into the stomach. The term PEG tube is often used to refer to any type of gastrostomy tube, though it technically describes those placed endoscopically (Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy). So from now on, PEG means all kinds of gastrostomy tubes.

Both deliver nutrition and medications, but the key difference is duration and invasiveness: NGTs are temporary, typically used for no longer than 4-6 weeks, while PEG tubes are meant for long-term feeding, usually more than four to six weeks, and allow patients greater comfort and mobility.

When should we consider NG tube placement in our patients?

Think about placing NGT tubes in the following situations:

- Patients who can’t safely swallow and need medication and nutrition administration, such as mechanically ventilated patients, severe stroke patients, or any other reason.

- Patients who need nutritional support when they cannot meet their caloric requirements through oral intake.

- Patients who need gastric decompression for bowel obstruction or ileus.

NGT is a short term solution for up to 4-6 weeks, if the patient needs enteral support beyond this timeframe, it’s time to consider transitioning to a PEG tube.

PEG tubes are our go-to for long-term feeding—anything beyond four to six weeks. This includes:

- Patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation who need to be transitioned to tracheostomy

- Patients with prolonged dysphagia from neurological conditions like ALS, advanced dementia, or severe stroke.

- It’s also indicated for head and neck cancer patients requiring radiation therapy, when we know they’ll need supplemental nutrition for more than four to six weeks.

- And finally, when patients are heading home, and will need continued enteral feeding support.

Precautions and contraindications

- NGTs are safe to place in most patients, and the absolute contraindications are limited. NGT placement is contraindicated in cases of facial trauma, nasal injury, abnormal nasal anatomy, or preexisting sinusitis. OGT (oral gastric tubes) can be alternatively considered in sedated patients, as it’s very uncomfortable to place in awake patients..

- Patients with recent GI bleed (especially peptic ulcer with a visible vessel) are considered a relative contraindication. Gastroenterology should be consulted if an NGT is absolutely necessary here!

- How about patients with liver cirrhosis? This is a frequently encountered situation! NG/OG tube placement is not absolutely contraindicated in cirrhotic patients! But, there is, of course, a higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly in those with esophageal varices, particularly within 48 hours of NG tube placement. So, enteric tube placement should be considered only after failure of oral supplementation, and close monitoring for bleeding is warranted.

- Percutaneous gastrostomy is strongly contraindicated:

- in cirrhosis with ascites, due to high complication and mortality rates.

- Active peritonitis, bowel ischemia, or mechanical intestinal obstruction.

Massive ascites and morbid obesity with a large panniculus are also recognized as major barriers to safe PEG placement.

Tube feeding system

NGT tubes come in different sizes, measured in French units. Common sizes range from 8 to 18 French. Smaller bore tubes, like 8-10 French, are more comfortable for patients and used primarily for feeding, while larger bore tubes, like 14-18 French, are used for gastric decompression. The tubes have depth markings along their length to help confirm proper positioning.

One of the most commonly used NGTs is the Salem sump tubes; these are large-bore tubes used mainly for gastric decompression and suction, featuring a double lumen with a blue vent to prevent mucosal damage.

The Dubhoff tube is a small-bore nasogastric feeding tube that is thinner and more flexible than standard nasogastric tubes, typically measuring 8-12 French in diameter. The tube features a weighted tungsten tip that helps it navigate through the gastrointestinal tract.

Choose small-bore soft tubes for nutrition and medication administration.

Choose large-bore, more rigid tubes for suction and gastric decompression.

In high-risk patients, such as liver cirrhosis or recent GI bleed, small-bore soft tubes are preferred and should be gently inserted.

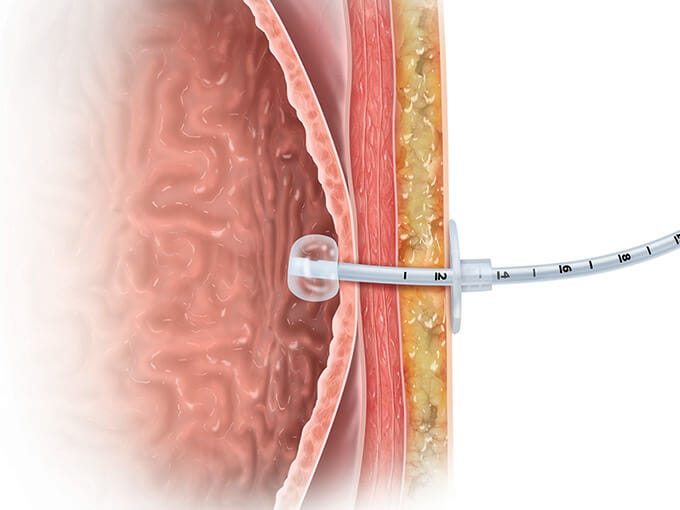

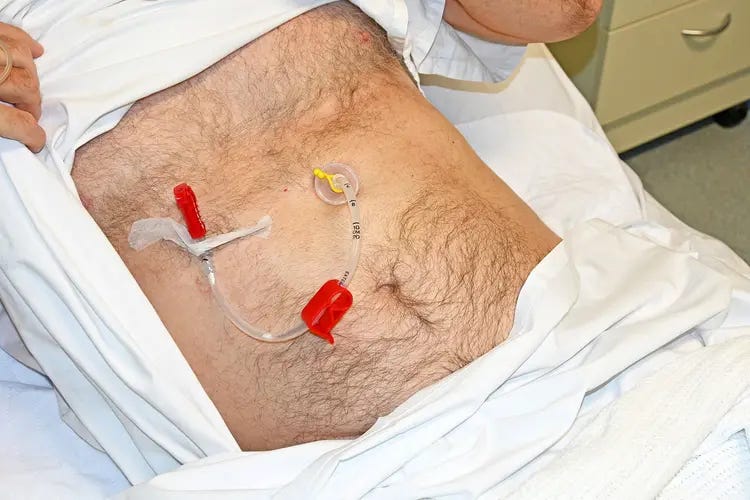

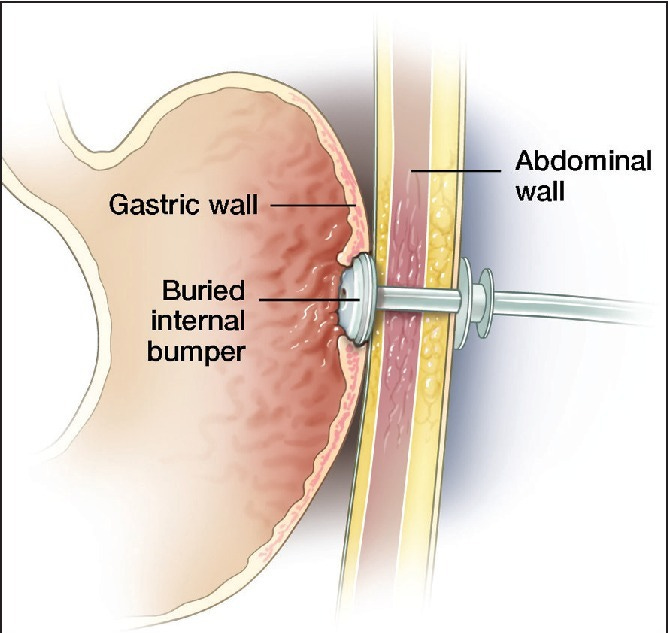

PEG tubes consist of several parts: an external bolster or bumper that sits against the abdominal wall, a long tube shaft, an internal bumper that sits against the stomach wall, and a feeding port with a cap. Some PEG tubes have a balloon instead of an internal bumper. The key is that the tube creates a stable tract between the stomach and skin.

Gastrostomy tubes can be placed endoscopically (PEG), surgically, or by interventional radiology; as we said earlier, the term ‘PEG tube’ specifically refers to tubes placed by the endoscopic technique, but is commonly used for all.

Modern feeding systems include gravity bags, pump-controlled systems, and bolus syringes. Pump-controlled feeding is preferred for continuous feeds as it provides consistent delivery rates and reduces aspiration risk compared to gravity feeding.

NGT positioning confirmation

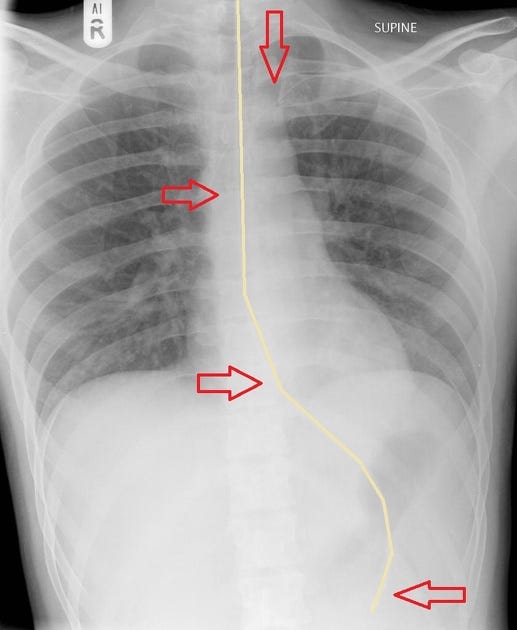

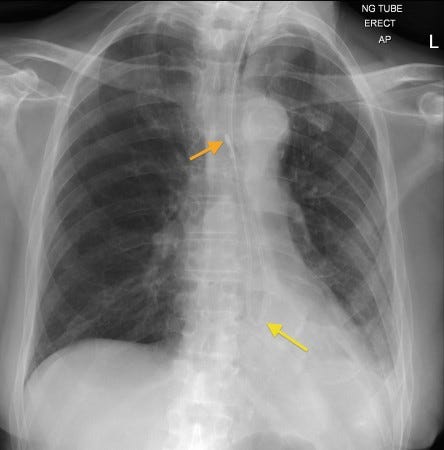

For NGT tubes, the gold standard is a chest X-ray showing the tube tip in the stomach, below the diaphragm, bisecting the carina. Bedside methods like pH testing and air insufflation are supplementary but should never replace X-ray confirmation for initial placement

Never use an NGT without X-ray confirmation

For PEG tubes, we typically start using them within a few hours of insertion. In practice, we must get the okay from the physician who performed the procedure before using it. We must also inspect the site for proper positioning of the external bumper; it should sit flush against the skin but not too tight, as excessive tension causes pressure necrosis, while too much slack allows leakage.

This image shows buried bumper syndrome, where the internal bumper has migrated into the gastric wall, causing pain and feeding intolerance.

The daily bedside checks when rounding on patients with feeding tubes

- Take all the necessary steps to minimize aspiration risk. Both NGT and PEG tubes carry aspiration risk, though PEG tubes generally have a lower risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia:

- Maintain the head-of-bed (HOB) elevation at 30–45 degrees during and after feeding and avoid supine positioning whenever possible.

- Pump-assisted continuous feeding is preferred over gravity or bolus feeds.

- In high-risk patients such as those with previous aspiration or gastroparesis, post-pyloric or jejunal placement should be considered.

- Inspect the insertion site for NGT/PEG:

- Check the nares for pressure ulcers, and ensure the tube is secured properly at the correct depth marking.

- For PEG: assess for redness, drainage, odor, or signs of infection. The site should be clean and dry. Also assess the pain or discomfort at the site.

- Next, evaluate the patient’s tolerance: any nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, or diarrhea? These suggest feeding intolerance.

- Nurses routinely assess tube patency by gently flushing with water. Tubes should be flushed with 30 mL of water before and after each feeding or medication administration. If resistance is met, the tube may be clogged.

Routine residual checks in continuous feeds are no longer recommended except in select cases (e.g., high risk for intolerance or if it’s still part of the ICU protocols).

Tube maintenance and troubleshooting

For NGT

- Clogged tubes are the most frequent issue. Prevention is key here: Flush with water regularly, crush medications, and never mix medications. If clogging occurs, try warm water flushes first. Pancreatic enzymes mixed with sodium bicarbonate can be used for stubborn clogs, but never use force, which can rupture the tube.

- Tube migration or dislodgment needs immediate attention. For NGT, if the tube is pulled out partially, never advance it blindly; remove it completely and replace it with radiographic confirmation.

For PEG tubes

If the tube falls out within the first four weeks before the tract matures, this is an emergency requiring immediate replacement, ideally within hours, as the tract closes rapidly. After four weeks, the tube can be replaced at the bedside with a Foley catheter temporarily until a new PEG tube is placed.

Residual volume troubleshooting (If you decided to check residual volume in continuous feed)

Remember that metoclopramide and erythromycin can be given every 6 hours as needed and remember that both can prolong QTc.

If intolerance persists despite prokinetics, switch to post-pyloric feeding

PEG site infections

Mild cellulitis around the site responds to oral antibiotics and local care. Severe infections, abscess formation, or necrotizing fasciitis require surgical consultation.

Buried bumper syndrome

presents with feeding intolerance, pain, and difficulty flushing. This requires endoscopic or surgical intervention to reposition or replace the tube.

The inpatient treatment of hypercalcemia

Hyperkalemia-induced EKG changes

The Proper Way to Replace Magnesium

Non-insulin diabetic medications

Chest Tubes & Pigtails: 5 Must-Know Tips for ICU Rotation

Mechanical Ventilation Made Simple: 9 Concepts Every Non-ICU Doc Should Know

NG Tube : 5 Things to know before your hospital rotations

Master ICU Vasopressor Management: 8 Shock Resuscitation Tips